The Princess Switch: The Netflix christmas Metaverse, or How Vanessa Hudgens Became a Cyborg 17/12/2021

And so the most wonderful time of the year has arrived once again: the air seems spiked by a mysterious drug bestowing on human masses the spirit of comforting forgetfulness. Christmas time, the celebration of white, patriarchal post-colonialism and white-saviour morality in a disguise of consumerist abundance. In this age of hyper-advanced capitalism, we are in our annual moment of financial harvest, when we take pleasure in a system which undoubtedly oppresses and exploits us, some much more than the others.

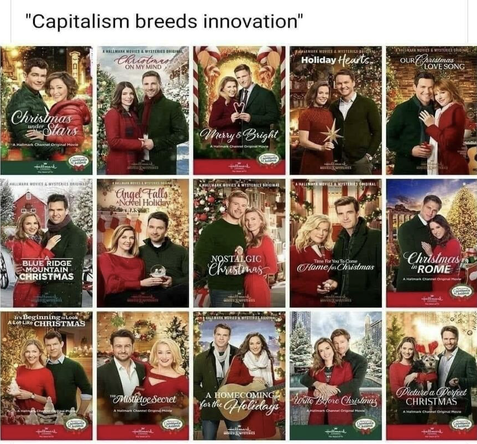

What could be more adequate in highlighting the essence of these pleasures than Christmas films, in particular the (in)famous Hallmark Christmas romances (not necessarily ONLY Hallmark, though they do have the monopoly)? Could we find a more perfect example of capitalism’s methods of profit-oriented race-to-unification than Hallmark films? The posters leave us no doubt:

What could be more adequate in highlighting the essence of these pleasures than Christmas films, in particular the (in)famous Hallmark Christmas romances (not necessarily ONLY Hallmark, though they do have the monopoly)? Could we find a more perfect example of capitalism’s methods of profit-oriented race-to-unification than Hallmark films? The posters leave us no doubt:

The plot is usually based on minimal variations of this story: the white female protagonist, quintessentially a career woman, travels from a big city to quintessential small town Americana to mend her broken life and enjoy quality time with her quintessential family. There she meets quintessential hunk with 3 days of beard growth, with whom she falls in love and, of course, decides to abandon her city life (along with her job) and quintessentially live happy-ever-small-town-after with said quintessential hunk.

Hallmark perfected the capitalist method of ignoring social, mental, emotional even logical complexity of story and character in favour of endless multiplication of The Same - same plot, same protagonists, same aesthetics - in the guise of Difference. However, swapping the actors (occasionally, daringly even their skin colour, see: Colin Lawrence’s phenomenon in Hallmark productions), town names, and what I am loathe to call ‘nuances’ of the script still propels The Same. The Same is empty albeit glossy and sparkly, and is pregnant with vastly outdated moral values, which nevertheless take central stage in Hallmark Christmas films through their focus on heteronormative patriarchal families.

Bearing in mind classic feminist television studies¹ we should restrain from dismissing the films as mindless entertainment and, indeed, as Sean Brayton suggests, they can offer a complex portrayal of the post-feminist negotiation of (white) feminnity. Again, whiteness here refers to power relations and signifies the Unitary structure where race (and ultimately gender) becomes a problem already overcome.

Hallmark perfected the capitalist method of ignoring social, mental, emotional even logical complexity of story and character in favour of endless multiplication of The Same - same plot, same protagonists, same aesthetics - in the guise of Difference. However, swapping the actors (occasionally, daringly even their skin colour, see: Colin Lawrence’s phenomenon in Hallmark productions), town names, and what I am loathe to call ‘nuances’ of the script still propels The Same. The Same is empty albeit glossy and sparkly, and is pregnant with vastly outdated moral values, which nevertheless take central stage in Hallmark Christmas films through their focus on heteronormative patriarchal families.

Bearing in mind classic feminist television studies¹ we should restrain from dismissing the films as mindless entertainment and, indeed, as Sean Brayton suggests, they can offer a complex portrayal of the post-feminist negotiation of (white) feminnity. Again, whiteness here refers to power relations and signifies the Unitary structure where race (and ultimately gender) becomes a problem already overcome.

The Princess Switch: The Trojan Horse inside Netflix’s Holiday Universe

In this article, however, we do not intend to dwell on the problematics (even if complex and productive) of race and gender representations in Hallmark Christmas films, but rather productively set them as a cultural backdrop which Netflix Christmas productions starring Vanessa Hudgens aesthetically refer to in order to create an IRONIC, self-referencing loop.

We can argue that the Netflix Christmas Universe implodes the rigid schema of Hallmark romance, tears it apart and puts it back together. They do not pretending to be monstrous and reflexive avant-garde pieces, but instead proudly embrace their existence as another product. Despite this, we intend to approach this holly-jolly Trojan Horse hidden in the belly of Netflix as having the power to dissect capitalist Christmas cheer.

In the first instalment of Vanessa Hudgens’ journey into Christmas Candyland, The Princess Switch (Mike Rohl, 2018), Stacey, a Chicago-based baker along with her sous chef Kevin (Nick Sagar) enter a baking competition in the fictional Kingdom of Belgravia. There, she magically encounters her doppelganger (from another fictional country, Montenaro) who also happens to be fiancé to a Belgravian prince, and who insists on swapping places with Stacey so she could experience the pleasures of non-royal life. Unsurprisingly, Stacey falls in love with Belgravian prince, whom she marries and Margaret finds love with Kevin and largely relinquishes her aristocratic lifestyle.

Then comes The Knight Before Christmas (Monika Mitchell, 2019) where Vanessa Hudgens falls in love with a knight Sir Cole (yes, circle) (Josh Whitehouse) who magically travels from 14th century to find his ultimate knight’s quest. The temporal loop and time travel, so smartly included in the knight’s name, are the background for a love story which lacks any earthly logic, creating a sweet world of a-signification.

Next we have The Princess Switch: Switched Again (Mike Rohl, 2020) where another Vanessa Hudgens arrives on the scene as Fiona Pembroke, Margaret’s cousin, a decadent and very much broke socialite. The plot of this instalment is grounded in Margaret’s coronation and portrays Fiona as an unruly, money-hungry vamp who doesn’t hesitate to kidnap her own cousin. In the most recent instalment, The Princess Switch 3: Romancing the Star (Mike Rohl, 2021), Fiona return to use her criminal past in order to help Margaret and Stacey locate a precious jewelled star, stolen by some villain or other.

What we deal with here is a complex multiverse where each piece references all others.

We can argue that the Netflix Christmas Universe implodes the rigid schema of Hallmark romance, tears it apart and puts it back together. They do not pretending to be monstrous and reflexive avant-garde pieces, but instead proudly embrace their existence as another product. Despite this, we intend to approach this holly-jolly Trojan Horse hidden in the belly of Netflix as having the power to dissect capitalist Christmas cheer.

In the first instalment of Vanessa Hudgens’ journey into Christmas Candyland, The Princess Switch (Mike Rohl, 2018), Stacey, a Chicago-based baker along with her sous chef Kevin (Nick Sagar) enter a baking competition in the fictional Kingdom of Belgravia. There, she magically encounters her doppelganger (from another fictional country, Montenaro) who also happens to be fiancé to a Belgravian prince, and who insists on swapping places with Stacey so she could experience the pleasures of non-royal life. Unsurprisingly, Stacey falls in love with Belgravian prince, whom she marries and Margaret finds love with Kevin and largely relinquishes her aristocratic lifestyle.

Then comes The Knight Before Christmas (Monika Mitchell, 2019) where Vanessa Hudgens falls in love with a knight Sir Cole (yes, circle) (Josh Whitehouse) who magically travels from 14th century to find his ultimate knight’s quest. The temporal loop and time travel, so smartly included in the knight’s name, are the background for a love story which lacks any earthly logic, creating a sweet world of a-signification.

Next we have The Princess Switch: Switched Again (Mike Rohl, 2020) where another Vanessa Hudgens arrives on the scene as Fiona Pembroke, Margaret’s cousin, a decadent and very much broke socialite. The plot of this instalment is grounded in Margaret’s coronation and portrays Fiona as an unruly, money-hungry vamp who doesn’t hesitate to kidnap her own cousin. In the most recent instalment, The Princess Switch 3: Romancing the Star (Mike Rohl, 2021), Fiona return to use her criminal past in order to help Margaret and Stacey locate a precious jewelled star, stolen by some villain or other.

What we deal with here is a complex multiverse where each piece references all others.

What is Different in The Princess Switch and Why is it Productive?

Vanessa Hudgens character can be seen as embodying a femininity that is imprisoned by ghd white, priapic/patriarchal heteronormative regime. Here we should evoke feminist thinker Luce Irigaray as well as her creative follower, Rosi Braidotti, who both claim that the mainstream discourse on gender and sexuality sees the feminine as the ‘lesser other’ of masculine. What we need to strive for instead is femininity allowed to act as Difference in itself, not imprisoned by current dialectics. This is evident in Hallmark Christmas films where the female protagonist can only achieve happiness through relationships with men. Moreover, we cannot let the post-feminist sensibility delude us, and we must be able to discern the neoliberal, post-gender and -race agenda which favours the masculine and is embodied by the concept of the girl-boss, whom female protagonists embody. Only when they went out into the world and achieved a successful career, can they return to their mythical small hometown to give it all up for a homebound life with prince charming.

Post-feminist sensibility is so dangerous because it induces in us self-denial through a neoliberal take on the concept of free will. The protagonists want to return to their hometowns and become modern housewives, the WANT to live in heterosexual relationships. They, WE (as the author of the article identifies as female) WANT to put our bodies through rigorous beauty regimes. What arises is a strange loop of signification, leaving us empty, ultimately body-less, with an overwhelming hunger that we temporarily satisfy with consumption – not necessarily actual but also virtual, through our consuming of media, usually digital media.

Netflix’s Christmas Universe can be seen as Alice’s Wonderland: it is the world of nonsense and paradox into which we enter through our digital screens. The logical and common-sense rules of dominant cinematic language are defied. Trying to make sense of continuity, documentary values or historical correctness? Not in Vanessa’s twee candyland: this is the delirious daydream of a teenage girl, and this is what governs the logic of this world.

This piece by Brian Abbey², who conducts a Freudian psychoanalysis of Vanessa’s character(s) in Princess Switch, although interesting, does not seem entirely fitting to this Wonderland. The phallic implications become a parody of themselves that Vanessa clearly embodies through her acting. There is no ID: there is pure madness, where Vanessa clones herself: it is as if she created many different social media profiles? A cyborg, conscious of her machinic parts.

Post-feminist sensibility is so dangerous because it induces in us self-denial through a neoliberal take on the concept of free will. The protagonists want to return to their hometowns and become modern housewives, the WANT to live in heterosexual relationships. They, WE (as the author of the article identifies as female) WANT to put our bodies through rigorous beauty regimes. What arises is a strange loop of signification, leaving us empty, ultimately body-less, with an overwhelming hunger that we temporarily satisfy with consumption – not necessarily actual but also virtual, through our consuming of media, usually digital media.

Netflix’s Christmas Universe can be seen as Alice’s Wonderland: it is the world of nonsense and paradox into which we enter through our digital screens. The logical and common-sense rules of dominant cinematic language are defied. Trying to make sense of continuity, documentary values or historical correctness? Not in Vanessa’s twee candyland: this is the delirious daydream of a teenage girl, and this is what governs the logic of this world.

This piece by Brian Abbey², who conducts a Freudian psychoanalysis of Vanessa’s character(s) in Princess Switch, although interesting, does not seem entirely fitting to this Wonderland. The phallic implications become a parody of themselves that Vanessa clearly embodies through her acting. There is no ID: there is pure madness, where Vanessa clones herself: it is as if she created many different social media profiles? A cyborg, conscious of her machinic parts.

The Christmas Land of Nonsense: In Search of the Copy of the Copy (with No Original)

If nothing makes sense, we are forced to create new concepts to describe this world, as none of the current linguistic tools seem fitting. Feminist theory must flexibly conjoin with queer theory to discern value of productive gender performance. Vanessa plays with her femininity, changes her look and costumes, and ultimately creates a rupture in our conception of the feminine.

We are no longer able to discern the original Vanessa Hudgens, or Stacey, as we deal not only with copies inside of the triptych Princess Switches, but also with Brooke Winters from The Knight Before Christmas, Vanessa Hudgens as a constructed personae, AND Vanessa Hudgens herself in our living reality. If there is no original and only cyborg-like, virtual copies then the reality itself, the Truth, is also heavily undermined. It would be interesting to conduct such film-philosophical analysis through Jean Baudrillard’s discussion on simulacra and simulacrum, but here we will allow ourselves to briefly mention these in order to further strengthen our insistence on the film’s complex self-awareness.

Vanessa Hudgens’s character in each of the Netflix Christmas films she graces implodes the signification. She breaks the strange loop, even if only very partially, to the degree its role as profit-making seasonal product allows.

Here, on Filmosophy, we believe that films not only portray reality but also create it. Love Actually (Richard Curtis, 2003), a staple holiday film since 2004, not just practically represented England 20 years ago, but also reinforced disgusting and hurtful dogmas and socially acceptable conducts, such as body-shaming, the negative serotypes of woman’s value as silent, caring, and accepting (of cheating and stalking). Luckily, the film is now more often being re-read and thus re-created by gender/race-conscious analysis.

Vanessa’s use of stereotypes is more creative and thus more productive, even if, as we mentioned before, the film does not pretend it is anything more than just a Christmas product to be consumed during this moment of capitalist forgetfulness.

We can even go as far as to discern Vanessa’s desire for polyamorous relationships which has not yet became entirely (or almost not at all) sanctioned by streaming platforms. What can a girl do, eh? She can clone herself and play with different modes of sexuality and femininity, however limited they are. In this article we focus mainly on the productive aspect of the Netflix franchise, but this does not imply that these limitations are not problematic, and that Vanessa can freely deconstruct her gender.

What is special about her transformation is the focus on the body: walking, speaking, body language. This is what guarantees the success of a switch. Thus, the films also embody a desire for freedom of the feminine body. To experiment and to push our body to its productive limits until it becomes something else. Until we become something else.

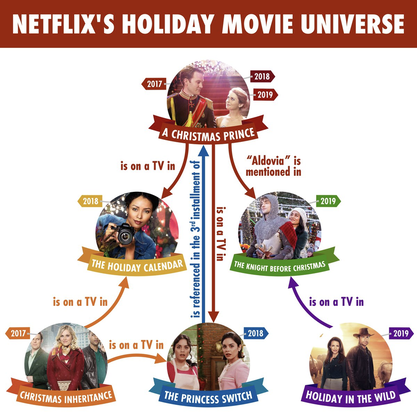

The schizophrenic temporality of capitalism, which empties time by dividing it into linear fragments - measurable and thus profitable - is crumbled by the film’s self-awareness of its implication in this process. The Christmas universe of Princess Switch diminishes the measurability of time by highlighting its nature as a part of bigger meta-verse, a multiverse which includes other Netflix films: A Christmas Prince (actual) whereas other film feature as films watched by characters. This diagram helpfully explains the complexities of the worlds inside of the worlds. Contradictions and impossibilities abound.

We are no longer able to discern the original Vanessa Hudgens, or Stacey, as we deal not only with copies inside of the triptych Princess Switches, but also with Brooke Winters from The Knight Before Christmas, Vanessa Hudgens as a constructed personae, AND Vanessa Hudgens herself in our living reality. If there is no original and only cyborg-like, virtual copies then the reality itself, the Truth, is also heavily undermined. It would be interesting to conduct such film-philosophical analysis through Jean Baudrillard’s discussion on simulacra and simulacrum, but here we will allow ourselves to briefly mention these in order to further strengthen our insistence on the film’s complex self-awareness.

Vanessa Hudgens’s character in each of the Netflix Christmas films she graces implodes the signification. She breaks the strange loop, even if only very partially, to the degree its role as profit-making seasonal product allows.

Here, on Filmosophy, we believe that films not only portray reality but also create it. Love Actually (Richard Curtis, 2003), a staple holiday film since 2004, not just practically represented England 20 years ago, but also reinforced disgusting and hurtful dogmas and socially acceptable conducts, such as body-shaming, the negative serotypes of woman’s value as silent, caring, and accepting (of cheating and stalking). Luckily, the film is now more often being re-read and thus re-created by gender/race-conscious analysis.

Vanessa’s use of stereotypes is more creative and thus more productive, even if, as we mentioned before, the film does not pretend it is anything more than just a Christmas product to be consumed during this moment of capitalist forgetfulness.

We can even go as far as to discern Vanessa’s desire for polyamorous relationships which has not yet became entirely (or almost not at all) sanctioned by streaming platforms. What can a girl do, eh? She can clone herself and play with different modes of sexuality and femininity, however limited they are. In this article we focus mainly on the productive aspect of the Netflix franchise, but this does not imply that these limitations are not problematic, and that Vanessa can freely deconstruct her gender.

What is special about her transformation is the focus on the body: walking, speaking, body language. This is what guarantees the success of a switch. Thus, the films also embody a desire for freedom of the feminine body. To experiment and to push our body to its productive limits until it becomes something else. Until we become something else.

The schizophrenic temporality of capitalism, which empties time by dividing it into linear fragments - measurable and thus profitable - is crumbled by the film’s self-awareness of its implication in this process. The Christmas universe of Princess Switch diminishes the measurability of time by highlighting its nature as a part of bigger meta-verse, a multiverse which includes other Netflix films: A Christmas Prince (actual) whereas other film feature as films watched by characters. This diagram helpfully explains the complexities of the worlds inside of the worlds. Contradictions and impossibilities abound.

Is Vanessa Hudgens a Cyborg?

What we want to concentrate on, however, is the films meta-thinking, which escapes the structures of production, exhibition, consumption. The film knows why it was made – like a cyborg that suddenly becomes conscious, a machine who knows it has been man-made for man’s pleasures (the usage of man is implicit here as to evoke the conceptual man that subsumes the feminine into himself). It can’t free herself entirely, but it can sabotage the structures from inside.

Here we benefit from Donna Haraway’s analysis of the cyborg in relation to feminism and social materialism. According to Haraway:

‘A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction’.³ In her piece she argues for the feminist embracement of cyborg figurations as it allows for liberation from the patriarchy by obliterating gender altogether. Hence, she also warns as that: 'The main trouble with cyborgs, of course, is that they are the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism'.

The female protagonists we encounter, as well as the Netflix films themselves, embody and embrace their cyborg nature, while simultaneously being conscious of their limitations as aforementioned offspring 'of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism.' They do, to a certain degree, expose gender as social performance and productively highlight the bodily, material nature of this process but do they leave class and race as untouched subjects? We argue for a productive focus on quazi—magical surrealism, a universe of interwoven fantasy (the small made-up monarchies, magical old characters a la Santa) and reality (Chicago). The Princess Switch universe feels like the fever dream of a girl/woman who falls into a post-feminist, post-human hole; a creative madness productively embraced by the films.

However and wherever on the privilege spectrum you situate yourself, the film’s pleasures will be embodied differently. For the target audience: cis, white, “female” and middle class, it can exist as the last the bastion where safety, however oppressive, is restored. The dreams that are forced into young girls’ minds about heterosexual love, family, successful careers are brought to life again, the oppression disguised as pleasures. Hallmark Christmas films – one of the last bastions of perverted lies, so joyfully embraced, awaited, and cherished. Princess Switch does not avoid this trap entirely, but it creates a small rupture in the matrix of Christmas romances; rupture that might pave the way for bolder and rebellious productions.

Here we benefit from Donna Haraway’s analysis of the cyborg in relation to feminism and social materialism. According to Haraway:

‘A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction’.³ In her piece she argues for the feminist embracement of cyborg figurations as it allows for liberation from the patriarchy by obliterating gender altogether. Hence, she also warns as that: 'The main trouble with cyborgs, of course, is that they are the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism'.

The female protagonists we encounter, as well as the Netflix films themselves, embody and embrace their cyborg nature, while simultaneously being conscious of their limitations as aforementioned offspring 'of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism.' They do, to a certain degree, expose gender as social performance and productively highlight the bodily, material nature of this process but do they leave class and race as untouched subjects? We argue for a productive focus on quazi—magical surrealism, a universe of interwoven fantasy (the small made-up monarchies, magical old characters a la Santa) and reality (Chicago). The Princess Switch universe feels like the fever dream of a girl/woman who falls into a post-feminist, post-human hole; a creative madness productively embraced by the films.

However and wherever on the privilege spectrum you situate yourself, the film’s pleasures will be embodied differently. For the target audience: cis, white, “female” and middle class, it can exist as the last the bastion where safety, however oppressive, is restored. The dreams that are forced into young girls’ minds about heterosexual love, family, successful careers are brought to life again, the oppression disguised as pleasures. Hallmark Christmas films – one of the last bastions of perverted lies, so joyfully embraced, awaited, and cherished. Princess Switch does not avoid this trap entirely, but it creates a small rupture in the matrix of Christmas romances; rupture that might pave the way for bolder and rebellious productions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY & Footnotes

1. See for instance: Ien Ang, Watching Dallas: Soap Opera and the Melodramatic Identification. NY: Methuen, 1985; Tania Modleski, Loving with a Vengeance: Mass-produced Fantasies for Women, (New York: Routledge. 1988).

2. Brian Abbey, https://thebrianabbey.medium.com/the-princess-switch-switched-again-and-freuds-psychoanalytic-theory-of-personality-7593c0f5c1b0.

3. Donna Haraway, 2016. Manifestly Haraway. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.p.5

2. Brian Abbey, https://thebrianabbey.medium.com/the-princess-switch-switched-again-and-freuds-psychoanalytic-theory-of-personality-7593c0f5c1b0.

3. Donna Haraway, 2016. Manifestly Haraway. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.p.5