Loving Vincent: The Art Of Movement 13/02/18

"There may be a great fire in our soul, yet no one ever comes to warm himself at it, and the passers-by see only a wisp of smoke" - Vincent Van Gogh

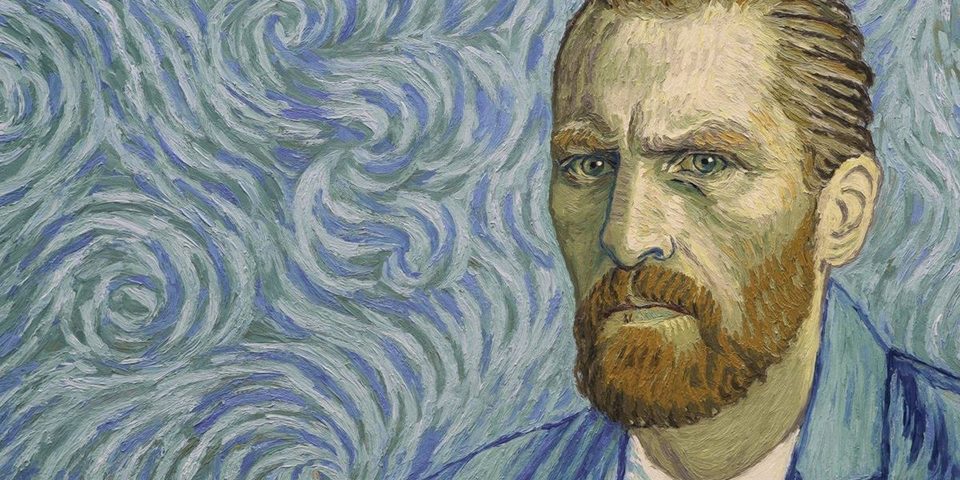

Loving Vincent is the Oscar-nominated animation film chronicling the journey of a postmaster's son trying to deliver Vincent Van Gogh’s final letter. It’s a film about the days and weeks leading up to Vincent’s suicide, and the small town gossip that exists around it. It’s also a film about his art, and how we reconcile that with his almost-as-famous mental health problems - talked about in the film much more than his paintings. At it’s heart too, the film has plenty to say about the nature of the movies as an art form.

The film was hand-painted, frame-by-frame, by a team of over 100 artists for years and, for the scenes taking place during the narrative, is in Van Gogh’s well known Post-Impressionist style. For flashbacks, a smoother black and white style is used. It’s an interesting choice, that has much more behind it than initially apparent.

It is only natural, that Van Gogh himself actually has very little to say in the film. Verbally, at least. It takes place after his death, and flashbacks are shown to us to be subjective to the person who’s telling them. The structure of the film lends itself to speculation and assumption made about Van Gogh via people who knew him, or had dealings with him. After all, this is all we can do ourselves. His art is famous for capturing the ecstatic beauty and movement and spectacle of life, noticing that everything is alive and so present. And despite this, we know he suffered too, that he was often intensely depressed and lonely. There’s a moment in the film that particularly springs to mind, when a young fisherman played by Aiden Turner talks of one of Van Gogh’s now famous paintings, simply exclaiming at how lonely he must have been to paint something like that.

Part of the enduring love of Van Gogh’s work is that people see in it such great truth of life and the world around us. He used his own perspective, and his own style to show us the world as he saw it. He fictionalised his world into the Post-Impressionist style, in order to show us fact. I guess, to show us what Herzog would call ecstatic truth. Loving Vincent does the same. The black & white, ultimately factual flashbacks are the boring truth of action, reaction, he did this, she did that. It gives us insight into the opinions of Vincent’s state towards the time of his death. But what does that really tell us about the man? Nothing of value, in my opinion. Or rather, nothing of inherent value, but its function in the film is what leads us to the understanding I’m about to try and convey. Because what really gives us the truth, the ecstatic truth, is the fictional story drawn in the frantic ceaseless movement of Van Gogh’s own famous style. We learn so much more about the man and how he saw the world by the performances of the actors and by his painting come to life! His paintings are already full of movement, it is heightened to beautiful levels by animation.

And doesn’t this speak so much about how cinema works? The line between fact and fiction is so often blurred in the movies. Documentaries reconstruct events, are structured and tell the story they want to tell. Fiction films make every effort to reflect real life and real people, so that we engage with them more and find ways to know ourselves and our world in them. In this way, they float and touch and join and separate in exciting ways, ways that can lead us to that ecstatic truth that Herzog famously speaks of. A truth that while not objective, can get at the heart of what really makes us who we are and how we connect with people around us. The persistent movement of life is the persistence of us to keep going, to create and connect and at least try to understand. That’s what great cinema captures, it’s what Van Gogh captured, and it’s what Loving Vincent captures too. It is about the art of movement, full of people running and walking and talking and meeting and leaving, full of conversations and dialogue that moves us, the audience. It’s a beautiful film, and it shows us that one great truth. The one we try to find and often can’t, the one that is all the more sweet for it’s transiency.

That it’s a beautiful life too.

Van Gogh saw it and showed us.

The movies can too,

Loving Vincent is evidence enough of that.

by Jack Buchanan

The film was hand-painted, frame-by-frame, by a team of over 100 artists for years and, for the scenes taking place during the narrative, is in Van Gogh’s well known Post-Impressionist style. For flashbacks, a smoother black and white style is used. It’s an interesting choice, that has much more behind it than initially apparent.

It is only natural, that Van Gogh himself actually has very little to say in the film. Verbally, at least. It takes place after his death, and flashbacks are shown to us to be subjective to the person who’s telling them. The structure of the film lends itself to speculation and assumption made about Van Gogh via people who knew him, or had dealings with him. After all, this is all we can do ourselves. His art is famous for capturing the ecstatic beauty and movement and spectacle of life, noticing that everything is alive and so present. And despite this, we know he suffered too, that he was often intensely depressed and lonely. There’s a moment in the film that particularly springs to mind, when a young fisherman played by Aiden Turner talks of one of Van Gogh’s now famous paintings, simply exclaiming at how lonely he must have been to paint something like that.

Part of the enduring love of Van Gogh’s work is that people see in it such great truth of life and the world around us. He used his own perspective, and his own style to show us the world as he saw it. He fictionalised his world into the Post-Impressionist style, in order to show us fact. I guess, to show us what Herzog would call ecstatic truth. Loving Vincent does the same. The black & white, ultimately factual flashbacks are the boring truth of action, reaction, he did this, she did that. It gives us insight into the opinions of Vincent’s state towards the time of his death. But what does that really tell us about the man? Nothing of value, in my opinion. Or rather, nothing of inherent value, but its function in the film is what leads us to the understanding I’m about to try and convey. Because what really gives us the truth, the ecstatic truth, is the fictional story drawn in the frantic ceaseless movement of Van Gogh’s own famous style. We learn so much more about the man and how he saw the world by the performances of the actors and by his painting come to life! His paintings are already full of movement, it is heightened to beautiful levels by animation.

And doesn’t this speak so much about how cinema works? The line between fact and fiction is so often blurred in the movies. Documentaries reconstruct events, are structured and tell the story they want to tell. Fiction films make every effort to reflect real life and real people, so that we engage with them more and find ways to know ourselves and our world in them. In this way, they float and touch and join and separate in exciting ways, ways that can lead us to that ecstatic truth that Herzog famously speaks of. A truth that while not objective, can get at the heart of what really makes us who we are and how we connect with people around us. The persistent movement of life is the persistence of us to keep going, to create and connect and at least try to understand. That’s what great cinema captures, it’s what Van Gogh captured, and it’s what Loving Vincent captures too. It is about the art of movement, full of people running and walking and talking and meeting and leaving, full of conversations and dialogue that moves us, the audience. It’s a beautiful film, and it shows us that one great truth. The one we try to find and often can’t, the one that is all the more sweet for it’s transiency.

That it’s a beautiful life too.

Van Gogh saw it and showed us.

The movies can too,

Loving Vincent is evidence enough of that.

by Jack Buchanan