Loving Vincent: Is It Still Cinema? 15/02/18

"In short, I want to reach the point where people say of my work, that man feels deeply and that man feels subtly. […] What am I in the eyes of most people? A nonentity or an oddity or a disagreeable person — someone who has and will have no position in society, in short a little lower than the lowest. […] Very well — assuming that everything is indeed like that, and then through my work I’d like to show what there is in the heart of such an oddity, such a nobody. This is my ambition, which is based less on resentment than on love in spite of everything, based more on a feeling of serenity than on passion. Even though I’m often in a mess, inside me there’s still a calm, pure harmony and music. In the poorest little house, in the filthiest corner, I see paintings or drawings. And my mind turns in that direction as if with an irresistible urge." (Letter 249 - Vincent to Theo)

This fragment of a letter that Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in 1882 exquisitely illustrates the painter's drive to create in spite of all the obstacles he encountered in his short life. The quotes were also used at the end of aunique, new film called Loving Vincent and left me in tears after the screening. Moreover, the painter's last letter to Theo serves to articulate a narration based on 'flashbacks', in which the son of Van Gogh's postman is forced to go through the artist's final steps to deliver to finally deliver it to psychiatrist, Dr. Paul Gachet.

Vincent Van Gogh was a man who famously sold only one painting while he was alive, battled with serious mental disorders and struggled with social ostracism but didn't stop painting until his death. Undeniably, his desire for the world to see how deeply and passionately he was experiencing reality came true. Today he is considered one of the greatest painters ever born, admired and known around the world. Apparently even Donald Trump is a fan of his work.

Van Gogh's life inspired many filmmakers and there are numerous films that explore different aspects of his career and troubled existence. To mention only few of them, there is Paul Cox's Vincent, Altman’s Vincent and Theo, Lust for Life directed by Vincent Minnelli or Akira Kurosawa's Dream. None of them, however, are as special as Loving Vincent. They differ in their technical approach and aspect of the part of Vincent's life they focus on. Loving Vincent is not only an animated film, but also a thriller and investigation story that explores the causes of the suicide of the artist. It is not a biographical film since it doesn't pretend to be a portrait of Van Gogh's life. In contrast, it provides possible interpretations of what his last days in Auvers might have been like by working on the basis of an alternative hypothesis to the official story of his suicide. In that manner it also constitutes a rigorous investigation, based on testimonies, statements and judicial reports that followed his death.

This fragment of a letter that Vincent Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in 1882 exquisitely illustrates the painter's drive to create in spite of all the obstacles he encountered in his short life. The quotes were also used at the end of aunique, new film called Loving Vincent and left me in tears after the screening. Moreover, the painter's last letter to Theo serves to articulate a narration based on 'flashbacks', in which the son of Van Gogh's postman is forced to go through the artist's final steps to deliver to finally deliver it to psychiatrist, Dr. Paul Gachet.

Vincent Van Gogh was a man who famously sold only one painting while he was alive, battled with serious mental disorders and struggled with social ostracism but didn't stop painting until his death. Undeniably, his desire for the world to see how deeply and passionately he was experiencing reality came true. Today he is considered one of the greatest painters ever born, admired and known around the world. Apparently even Donald Trump is a fan of his work.

Van Gogh's life inspired many filmmakers and there are numerous films that explore different aspects of his career and troubled existence. To mention only few of them, there is Paul Cox's Vincent, Altman’s Vincent and Theo, Lust for Life directed by Vincent Minnelli or Akira Kurosawa's Dream. None of them, however, are as special as Loving Vincent. They differ in their technical approach and aspect of the part of Vincent's life they focus on. Loving Vincent is not only an animated film, but also a thriller and investigation story that explores the causes of the suicide of the artist. It is not a biographical film since it doesn't pretend to be a portrait of Van Gogh's life. In contrast, it provides possible interpretations of what his last days in Auvers might have been like by working on the basis of an alternative hypothesis to the official story of his suicide. In that manner it also constitutes a rigorous investigation, based on testimonies, statements and judicial reports that followed his death.

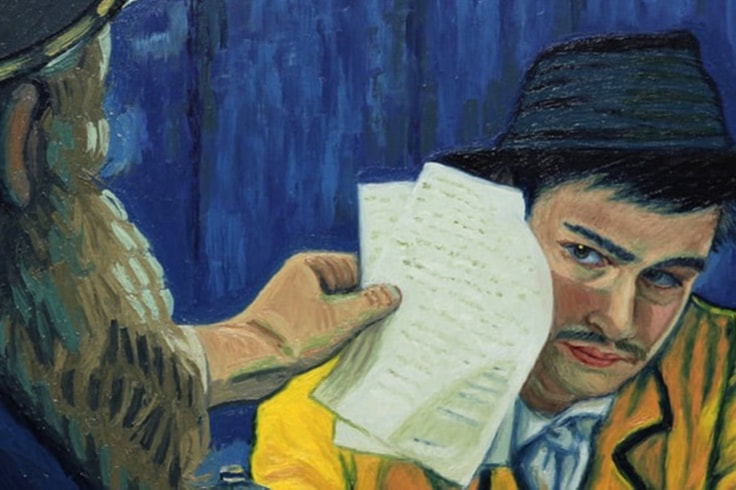

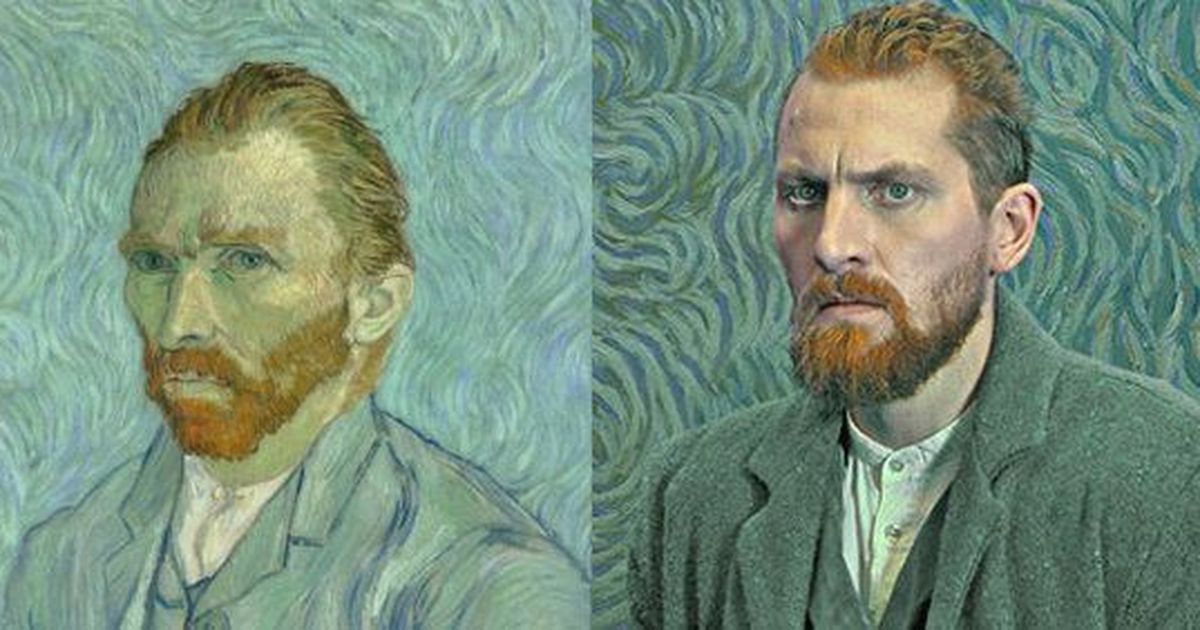

Loving Vincent was initially shot with actors and then painted by hand, frame-by-frame. The animation of these painted representations makes the characters integrate perfectly into the painting, obtaining a final result that is like Van Gogh's paintings being brought to life in front of our eyes.

The film was founded by the Polish Film Institute and a Kickstarter campaign, and was written and directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman. There were 125 artists who painted a total of 65,000 frames and it took them 6 years to make Loving Vincent happen, to bring Van Gogh's paintings to life. We can imagine the enormity of the work that was required to finish the film if we bear in mind that 12 frames are needed to make every second of footage. 94 paintings by Van Gogh appear in this unprecedented animation.

The process of portraying protagonists was also difficult and time-consuming: the artists had to integrate Van Gogh's characteristic stroke and, at the same time, to structure faces enough without losing their expressiveness in the animation. Another challenge was to adapt the different sizes of the Van Gogh canvases to a standard of 103 × 60 cm, the measure required to adapt to the more squared format that they chose for the film. Then there was also the problem of 'the invasions' that took place when a character painted with a certain style moved to get into another painting with a different style. Moreover, when the narrative required, there was a need to change a picture that reflected a daytime scene to a nocturnal representation, or from autumn and winter to other seasons.

It is impossible to deny that Loving Vincent is a film that must be seen not only by art lovers but by anyone who simply appreciates beauty. However, the final product, as a film, is far from perfect.

The film was founded by the Polish Film Institute and a Kickstarter campaign, and was written and directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman. There were 125 artists who painted a total of 65,000 frames and it took them 6 years to make Loving Vincent happen, to bring Van Gogh's paintings to life. We can imagine the enormity of the work that was required to finish the film if we bear in mind that 12 frames are needed to make every second of footage. 94 paintings by Van Gogh appear in this unprecedented animation.

The process of portraying protagonists was also difficult and time-consuming: the artists had to integrate Van Gogh's characteristic stroke and, at the same time, to structure faces enough without losing their expressiveness in the animation. Another challenge was to adapt the different sizes of the Van Gogh canvases to a standard of 103 × 60 cm, the measure required to adapt to the more squared format that they chose for the film. Then there was also the problem of 'the invasions' that took place when a character painted with a certain style moved to get into another painting with a different style. Moreover, when the narrative required, there was a need to change a picture that reflected a daytime scene to a nocturnal representation, or from autumn and winter to other seasons.

It is impossible to deny that Loving Vincent is a film that must be seen not only by art lovers but by anyone who simply appreciates beauty. However, the final product, as a film, is far from perfect.

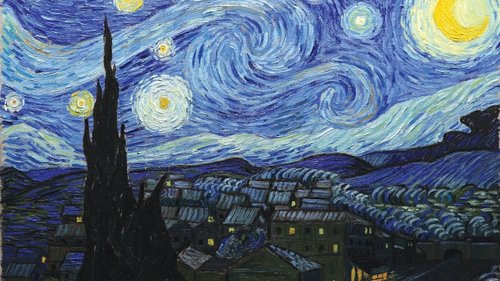

I discovered the paintings of Vincent Van Gogh when I was a little girl while browsing through my mum’s art books and couldn’t take my eyes off them for hours. I was hypnotized by the movement and emotions evoked by the visible brush strokes and vivid colors. I didn't have much knowledge about the history of art, painting techniques, and Van Gogh himself but the feelings it provoked in my young heart stay with me until this day and resurrect with the same dynamism every time I look at the swirling clouds of Wheat Field with Cypresses and Starry Night.

That said, it is not surprising that I have been beyond excited for Loving Vincent since I saw the trailer in 2016. Sadly, when it finally debuted in British cinemas, I missed it and wasn't able to watch until last week. Auspiciously, I managed to catch one of the last chances to see it on the big screen in Seville and I have to admit that I've got some very mixed feelings.

Undoubtedly, the visual aspect of the film is marvelous but watching it felt more like a visit to the art gallery than a trailblazing cinema experience. The story line is so weak that I quickly stopped paying any attention to the plot and concentrated on admiring the tremendous wok that was done by the creators of the film. Moreover, even the avant-garde experiments with style and form get a bit agitating after a while. It seemed like a weird dream in which I'm not sure I want to wake up or keep dreaming. However, the feelings that Van Gogh's paintings always provoke in me were still there during the film. The emotions associated with unspeakable loneliness, sadness, passion, love, joy – I felt it all watching Loving Vincent, and cried like a baby at the end.

Therefore, it imposes a very important question about cinema: what requirements should moving pictures meet to be called 'films'? Interestingly, early abstractionist and expressionist short films made in the 1910s and 1920s (by, for instance, Lois Weber or Man Ray) address the same concerns. Does film need to have a plot, a narrative in the traditional, structured sense? Loving Vincent let Van Gogh's paintings to speak to us, this is Vincent's story told through his own eyes and heart.

by Paulina

That said, it is not surprising that I have been beyond excited for Loving Vincent since I saw the trailer in 2016. Sadly, when it finally debuted in British cinemas, I missed it and wasn't able to watch until last week. Auspiciously, I managed to catch one of the last chances to see it on the big screen in Seville and I have to admit that I've got some very mixed feelings.

Undoubtedly, the visual aspect of the film is marvelous but watching it felt more like a visit to the art gallery than a trailblazing cinema experience. The story line is so weak that I quickly stopped paying any attention to the plot and concentrated on admiring the tremendous wok that was done by the creators of the film. Moreover, even the avant-garde experiments with style and form get a bit agitating after a while. It seemed like a weird dream in which I'm not sure I want to wake up or keep dreaming. However, the feelings that Van Gogh's paintings always provoke in me were still there during the film. The emotions associated with unspeakable loneliness, sadness, passion, love, joy – I felt it all watching Loving Vincent, and cried like a baby at the end.

Therefore, it imposes a very important question about cinema: what requirements should moving pictures meet to be called 'films'? Interestingly, early abstractionist and expressionist short films made in the 1910s and 1920s (by, for instance, Lois Weber or Man Ray) address the same concerns. Does film need to have a plot, a narrative in the traditional, structured sense? Loving Vincent let Van Gogh's paintings to speak to us, this is Vincent's story told through his own eyes and heart.

by Paulina