Paulina's Gore Corner Episode 6 - Martyrs And The Demystification of Femininity 22/09/18

Paul Laugier’s French horror Martyrs (2008) was the subject of my analysis in the last instalment of Paulina’s Gore Corner. In order to decode the underlying meaning, I found Deleuzian ideas on schizoanalysis and body-without-organs helpful to understand the way in which the spectator is implicated in the heroine’s suffering via cinematography, framing and sound design. I felt, however, that in my analysis I have overlooked the central aspect of the film - its representation of gender, or more specifically, representation of femininity. Martyrs does the opposite of what horror and mainstream cinema in general do - it places the woman as the most powerful figure, completely desexualises female bodies, and instead offers a ‘bare’ take on womanhood. Without the aspect of sex or sexualised eroticism, the viewer is able to truly see the socio-cultural mechanisms that affect what it means to be a woman.

GENDER POWER BALANCE

It is useful at this point to quote Robin Wood, one of the most influential horror critics, who reflected on the gender power balance:

‘In a male-dominated culture, where power, money, law, and social institutions are controlled by past, present, and future patriarchs, women as the other assumes particular significance. The dominant images of women in our culture are entirely male created and male controlled. Women’s autonomy and independence are denied; on to women men project their own innate, repressed femininity in order to disown it as inferior.’ (Wood 1986: 74)

Indeed, the structure of most horror is centred around a passive, helpless female victim or ‘monstrous-feminine’ - that representation of male castration anxiety. Gory depiction of female suffering is definitely not something new, however, and the visceral, graphic portrayal of torture executed on young women is what the viewers found most problematic. Moreover negative reviews often point out that Laugier eroticises or even glorifies the violence against women. These arguments echo old debates about the slasher films and its approach to the representation of femininity. I would agree with the notion of eroticised and romantic violence in Martyrs but I am also far from dismissing the film as misogynistic or exploitative. In contrast, I see Laugier’s film as a text that obliterates the known patriarchal order, overturns the power balance between both femininity and masculinity and male-female.

Martyrs is constructed of multiple layers that illustrate how the dominant patriarchal capitalist society works. As the narrative progresses, the film progressively sheds its complicated coating leaving us, literally, with the bare flesh of womanhood. In this article I intend to focus exclusively on Martyrs representation of gender with a special regard to femininity as the film is dominated by female characters, and the remaining males are rather insignificant apart from their physical strength. I argue that the film annihilates the rules created by thousands of years of patriarchy by juxtaposing the film with the main theories of horror that simply do not offer help in the case of Martyrs. What is so special, disturbing, and even unthinkable about Laugier’s film is the fact that women are not narratively placed ‘in relation to men’, but in a ‘society’ organised around matriarchate. The fact that our understanding of woman can only exist as an opposition to man explains why Martyrs is so indigestible for many viewers. We are used to watching men violate women, both literally and ideologically, but what if there are women who violate women on the order of the woman? It is important to see the male characters present in Martyrs as executors of violence that was organised and ordered by females. Their physical strength is used only as tool, an instrument that belongs to woman.

‘In a male-dominated culture, where power, money, law, and social institutions are controlled by past, present, and future patriarchs, women as the other assumes particular significance. The dominant images of women in our culture are entirely male created and male controlled. Women’s autonomy and independence are denied; on to women men project their own innate, repressed femininity in order to disown it as inferior.’ (Wood 1986: 74)

Indeed, the structure of most horror is centred around a passive, helpless female victim or ‘monstrous-feminine’ - that representation of male castration anxiety. Gory depiction of female suffering is definitely not something new, however, and the visceral, graphic portrayal of torture executed on young women is what the viewers found most problematic. Moreover negative reviews often point out that Laugier eroticises or even glorifies the violence against women. These arguments echo old debates about the slasher films and its approach to the representation of femininity. I would agree with the notion of eroticised and romantic violence in Martyrs but I am also far from dismissing the film as misogynistic or exploitative. In contrast, I see Laugier’s film as a text that obliterates the known patriarchal order, overturns the power balance between both femininity and masculinity and male-female.

Martyrs is constructed of multiple layers that illustrate how the dominant patriarchal capitalist society works. As the narrative progresses, the film progressively sheds its complicated coating leaving us, literally, with the bare flesh of womanhood. In this article I intend to focus exclusively on Martyrs representation of gender with a special regard to femininity as the film is dominated by female characters, and the remaining males are rather insignificant apart from their physical strength. I argue that the film annihilates the rules created by thousands of years of patriarchy by juxtaposing the film with the main theories of horror that simply do not offer help in the case of Martyrs. What is so special, disturbing, and even unthinkable about Laugier’s film is the fact that women are not narratively placed ‘in relation to men’, but in a ‘society’ organised around matriarchate. The fact that our understanding of woman can only exist as an opposition to man explains why Martyrs is so indigestible for many viewers. We are used to watching men violate women, both literally and ideologically, but what if there are women who violate women on the order of the woman? It is important to see the male characters present in Martyrs as executors of violence that was organised and ordered by females. Their physical strength is used only as tool, an instrument that belongs to woman.

THE FUTURE IS FEMALE

As the gender norms are entirely reverted, the film plays with the idea of androgyny, clearly depicted in the representation of tortured women and Mademoiselle. Martyrs searches for ‘future female’ by reducing her to the Deleuzian body-without-organs and lays bare the unspoken process of ‘becoming-woman’. The film, therefore, is the illustration of gender being culturally and socially constructed. It deconstructs what the society tries to hide, it ridicules the patriarchal system by exhibiting its lack coherency and ‘real’ validity . Martyrs demystifies gender as a product of a heteronormative, patriarchal paradigm and deconstructs the process of its creation through Anna’s martyrdom.

Although the above arguments are problematised by the subtle allusions to race (Lucie’s and Anna’s darker skin colour) and sexuality (Anna’s attempt to engage in ‘sexualised’ activity with Lucie), the main reference point is femininity as a social fabrication and its demystification. Nevertheless, significant distinction has to be made between differences in portrayal of that deconstruction in the narratives of Anna and Lucie. The latter somehow fits into the known theories of film and gender linking it to psychoanalysis with the representative of Lucy as a ‘phallic woman’, ’monstrous feminine’ or ‘final girl’. The manifestation of woman’s repressed traumas in the figure of the Creature also finds detailed explanation in Freud’s approach. On the other hand, Anna’s narrative is utterly visceral and unique. My hands were clenched, while I was trying to helplessly find academic background to discuss her cinematic martyrdom, and it became a common occurrence on my recent research journey that I found Deleuze’s and Guittari’s ideas extremely helpful.

Laugier showed enormous bravery when he decided not only make a strong female horror film but also to set its action in the realm of female dominance. In an interview with Ryan Rotten, he noted (Green, 2011: 23):

Women were the ones who made me connect to horror and fantastic culture at first. Like a primitive image, watching Mia Farrow, short-haired, in melancholic pieces of work like Rosemary’s Baby and The Haunting of Julia (Full Circle) inspired forever my way of viewing the world. I mean, it blew my mind to a point that, until now, what is sold as reality doesn’t seem as real to me as a lot of things that were told by Polanski, Argento, Carpenter, Francis Bacon and dozens of great artists. It’s not a way for me to escape from the real world, it’s not like being close to other people. It’s just a way to be closer to what I find true and beautiful in life. (n.p.)

This view of femininity may be problematic as it indicates that there is a ‘true’ way to represent feminism and therefore ignores its complexity. Nevertheless, the impact that horror heroines had on the director is worth bearing in mind while thinking about the violence he inflicts on the female characters in Martyrs.

Although the above arguments are problematised by the subtle allusions to race (Lucie’s and Anna’s darker skin colour) and sexuality (Anna’s attempt to engage in ‘sexualised’ activity with Lucie), the main reference point is femininity as a social fabrication and its demystification. Nevertheless, significant distinction has to be made between differences in portrayal of that deconstruction in the narratives of Anna and Lucie. The latter somehow fits into the known theories of film and gender linking it to psychoanalysis with the representative of Lucy as a ‘phallic woman’, ’monstrous feminine’ or ‘final girl’. The manifestation of woman’s repressed traumas in the figure of the Creature also finds detailed explanation in Freud’s approach. On the other hand, Anna’s narrative is utterly visceral and unique. My hands were clenched, while I was trying to helplessly find academic background to discuss her cinematic martyrdom, and it became a common occurrence on my recent research journey that I found Deleuze’s and Guittari’s ideas extremely helpful.

Laugier showed enormous bravery when he decided not only make a strong female horror film but also to set its action in the realm of female dominance. In an interview with Ryan Rotten, he noted (Green, 2011: 23):

Women were the ones who made me connect to horror and fantastic culture at first. Like a primitive image, watching Mia Farrow, short-haired, in melancholic pieces of work like Rosemary’s Baby and The Haunting of Julia (Full Circle) inspired forever my way of viewing the world. I mean, it blew my mind to a point that, until now, what is sold as reality doesn’t seem as real to me as a lot of things that were told by Polanski, Argento, Carpenter, Francis Bacon and dozens of great artists. It’s not a way for me to escape from the real world, it’s not like being close to other people. It’s just a way to be closer to what I find true and beautiful in life. (n.p.)

This view of femininity may be problematic as it indicates that there is a ‘true’ way to represent feminism and therefore ignores its complexity. Nevertheless, the impact that horror heroines had on the director is worth bearing in mind while thinking about the violence he inflicts on the female characters in Martyrs.

BECOMING-WOMAN

The film starts with an intense sequence in which Lucie escapes from her torture chamber. From the very beginning, the physical and mental terror experienced by the heroine is overwhelmingly embodied in the film. In a series of fast, handheld tracking shots we watch as a terrified androgynous figure desperately runs for freedom. Through the camera techniques and sound design, the viewer connects with Lucie on a corporeal level and consequently ‘become’ her. At this point, the audience don’t consider the character in terms of gender as all the attributes of femininity were stolen from Lucie: her hair was shaved, she lacks breasts, her head and body is deformed, covered in blood with visible signs of abuse on her body. We identify with the character but it is complicated by its androgynous representation. It is helpful, therefore, to refer to Deleuze’s and Guattari’s notion of ‘becoming’ defined as’ extreme contiguity within a coupling of two sensation without resemblance’. As Patricia Pisters insightfully noted, ‘all becomings seem to be initiated by becoming-woman’(2003:106). Lucie’s initial escape may be read as her first step on the journey of constant becoming. According to Ian Buchanan (cited in Pisters, 2003: 106):

From a certain point of view, the most deeply utopian texts are not those that propose or depict a better society, but those who carry out the most thoroughgoing destruction of present society. For Deleuze, however, simply seeing/transgressing limit is not enough to release us from perceptibility because it preserves the idea of limit. One must do more, but what? The answer is becoming-woman, where becoming woman is the basis of total critique.

Indeed, Laugier investigates what it means to do ‘more’ and this is where Deleuze’s concept of Becoming-Woman comes helpful. According to Deleuze and Guattari explain becoming-woman as ‘a process of microfemininity that can take place in both female and male bodies (as well as in other sorts of bodies)’ (Pisters, 2003: 111). I propose that the key female characters in Martyrs, Lucie, Anna and Mademoiselle, may be considered as constituting one, disparate body. Each heroine resembles the main stages of a woman’s life: childhood, maturity and old age which consequently highlights the elasticity of the body and fluidity of personal identity which is undermined by ‘paradoxic movements of becoming’ (Pisters, 2003:109). Moreover, by refusing Anna rights to her own body, the film puts the emphasis on the socially and culturally constructed order that treats both male and female bodies as belonging to the dominant system. In A Thousand Plateaus Deleuze and Guattari (cited in Pisters, 2003:111) explain:

The question is fundamentally that of the body - the body they steal from us in order to fabricate opposable organisms. The body is stolen first from a girl: stop behaving like that, you’re not a girl anymore, you’re not a tomboy, etc. The girl’s becoming is stolen first in order to impose a history to prehistory upon her. The boy’s turn comes next, but it is to use the girl as an example, by pointing to the girl as the object of his desire, that an opposed organism, a dominant history is fabricated him too. The girl is the first victim, but she must also serve as an example and a trap. This is why, conversely, the reconstruction of the body as a Body without Organs, the an organism of the body, is inseparable from a becoming a woman, or a production of molecular woman.

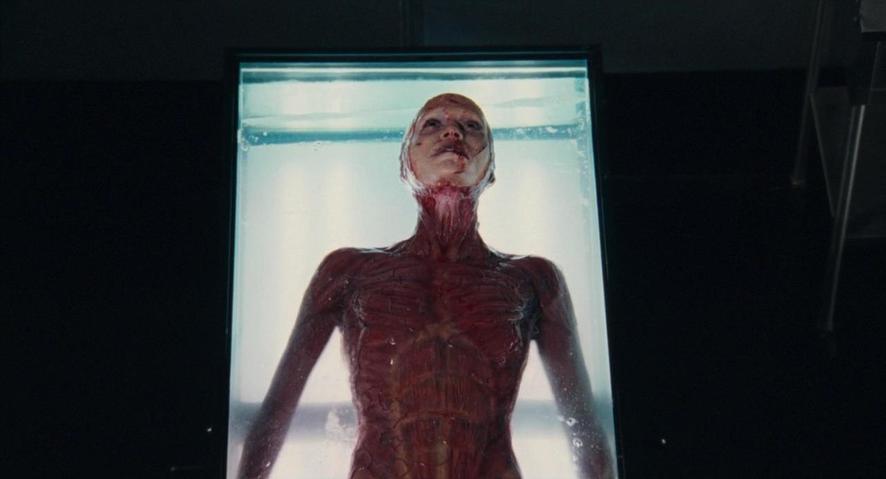

Body-without-organs, the ‘body that resists single and fixed identities’, and ‘opposes the limits of the organism’ ‘is the zero degree of the body, where every body has its potential’ (Pisters, 110). In Martyrs, the BwO is manifested through Anna’s flayed body while she gazes into infinity. There are also the bodies of two other tortured women, the Creature and the Victim, which also may be seen as BwO, but emptied, ‘bodies cannot produce any intestines and flows but disappear in a black hole’ (Pisters, 110). I argue that these Bodies without Organs are the symbol of a new facet of feminism, where perspective shifts in Deleuze’s direction. Having said that I am going to briefly justify this statement but I’m aware that length of this article will not let me fully explore it.

From a certain point of view, the most deeply utopian texts are not those that propose or depict a better society, but those who carry out the most thoroughgoing destruction of present society. For Deleuze, however, simply seeing/transgressing limit is not enough to release us from perceptibility because it preserves the idea of limit. One must do more, but what? The answer is becoming-woman, where becoming woman is the basis of total critique.

Indeed, Laugier investigates what it means to do ‘more’ and this is where Deleuze’s concept of Becoming-Woman comes helpful. According to Deleuze and Guattari explain becoming-woman as ‘a process of microfemininity that can take place in both female and male bodies (as well as in other sorts of bodies)’ (Pisters, 2003: 111). I propose that the key female characters in Martyrs, Lucie, Anna and Mademoiselle, may be considered as constituting one, disparate body. Each heroine resembles the main stages of a woman’s life: childhood, maturity and old age which consequently highlights the elasticity of the body and fluidity of personal identity which is undermined by ‘paradoxic movements of becoming’ (Pisters, 2003:109). Moreover, by refusing Anna rights to her own body, the film puts the emphasis on the socially and culturally constructed order that treats both male and female bodies as belonging to the dominant system. In A Thousand Plateaus Deleuze and Guattari (cited in Pisters, 2003:111) explain:

The question is fundamentally that of the body - the body they steal from us in order to fabricate opposable organisms. The body is stolen first from a girl: stop behaving like that, you’re not a girl anymore, you’re not a tomboy, etc. The girl’s becoming is stolen first in order to impose a history to prehistory upon her. The boy’s turn comes next, but it is to use the girl as an example, by pointing to the girl as the object of his desire, that an opposed organism, a dominant history is fabricated him too. The girl is the first victim, but she must also serve as an example and a trap. This is why, conversely, the reconstruction of the body as a Body without Organs, the an organism of the body, is inseparable from a becoming a woman, or a production of molecular woman.

Body-without-organs, the ‘body that resists single and fixed identities’, and ‘opposes the limits of the organism’ ‘is the zero degree of the body, where every body has its potential’ (Pisters, 110). In Martyrs, the BwO is manifested through Anna’s flayed body while she gazes into infinity. There are also the bodies of two other tortured women, the Creature and the Victim, which also may be seen as BwO, but emptied, ‘bodies cannot produce any intestines and flows but disappear in a black hole’ (Pisters, 110). I argue that these Bodies without Organs are the symbol of a new facet of feminism, where perspective shifts in Deleuze’s direction. Having said that I am going to briefly justify this statement but I’m aware that length of this article will not let me fully explore it.

THE THIEVES OF THE BODY

As Lucie escapes into ‘freedom’, she, and consequently the viewer, takes their first step into becoming-woman. The notion of ‘freedom’ is, however, ambiguous as it requires the girl to conform to norms and rules set by a patriarchal society. In a series of super-8 shots, we observe Lucie as she struggles to fight her traumatic memories in the orphanage. The male presenter guides us through the building in which the girl was kept. He’s one of the few male characters in the film and, like the rest of them he doesn't bear much significance; he is only a passive observer, unable to even partially grasp the horrors Lucie experienced. It is significant that after the girl was rescued, her socialisation into patriarchal society began. We are now able to clearly identify Lucie as a girl with her longer hair and feminine clothes and therefore her process of becoming-woman evolves. Additionally, in the orphanage Lucie befriends Anna, a little girl who was deeply moved by Lucie’s experiences and the only person who has the privilege to enter Lucie’s world. Anna instantly becomes a unique mother figure for the traumatised girl and they remain inseparable.

The scene in which little Anna is interrogated by police officers and medical personnel is significant as it is one of the rare opportunities in the film to analyse the power balance between male and female. It is crucial to acknowledge that while confronted with these male representatives of patriarchal authority, the power balance conveyed through ‘gaze’ is controlled by little Anna. Laura Mulvey in her groundbreaking essays explains the importance of looking:

‘In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.’ (Mulvey, 1999: 837)

In contrast to the vast majority of cultural texts, Martyrs positions female figures as the main source of power. In the scene mentioned above, Anna is the bearer of the dominant gaze; she’s the only one who earned the entrance to Lucie’s head. Moreover, the close up of the policeman’s face while he questions Anna may be revealing. Instead of looking at the girl, he is filmed looking down so the viewer can’t even see his eyes. Is he not able to look at her as he is not ready to confront the knowledge she possesses?

The reversal of gendered power balances and roles is even more explicitly highlighted in the scene where we meet the family who tortured Lucie in her childhood. Interestingly, it is the man, father, who occupies domestic space while cooking breakfast for the family and the mother is engaged in masculine, physical activity as she digs a hole in the garden. When she enters the house, she amusedly displays a dead mouse, puts it on the table plays with it, proud of the effect her transgressive toy has on the other family members.

It is the mother who is a bearer of dominant gaze while father is filmed looking down, not able to confront his gaze with anyone. Moreover, it is him, the man, who dies first when Lucie, a phallic woman, unexpectedly appears in the house with a shotgun.

The male characters in Martyrs are degraded to helpless, passive observers or literal instruments in the hands of women. Their physical strength is not something that bears any political power or stands as criterion for superiority. It echoes the ideas of second-wave feminism that considered Male muscles ‘culturally encouraged, through breeding, diet, and exercise’ and physical strength is nil longer really [politically relevant within ‘civilisation’ (Millet, 2000: 27).

The scene in which little Anna is interrogated by police officers and medical personnel is significant as it is one of the rare opportunities in the film to analyse the power balance between male and female. It is crucial to acknowledge that while confronted with these male representatives of patriarchal authority, the power balance conveyed through ‘gaze’ is controlled by little Anna. Laura Mulvey in her groundbreaking essays explains the importance of looking:

‘In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.’ (Mulvey, 1999: 837)

In contrast to the vast majority of cultural texts, Martyrs positions female figures as the main source of power. In the scene mentioned above, Anna is the bearer of the dominant gaze; she’s the only one who earned the entrance to Lucie’s head. Moreover, the close up of the policeman’s face while he questions Anna may be revealing. Instead of looking at the girl, he is filmed looking down so the viewer can’t even see his eyes. Is he not able to look at her as he is not ready to confront the knowledge she possesses?

The reversal of gendered power balances and roles is even more explicitly highlighted in the scene where we meet the family who tortured Lucie in her childhood. Interestingly, it is the man, father, who occupies domestic space while cooking breakfast for the family and the mother is engaged in masculine, physical activity as she digs a hole in the garden. When she enters the house, she amusedly displays a dead mouse, puts it on the table plays with it, proud of the effect her transgressive toy has on the other family members.

It is the mother who is a bearer of dominant gaze while father is filmed looking down, not able to confront his gaze with anyone. Moreover, it is him, the man, who dies first when Lucie, a phallic woman, unexpectedly appears in the house with a shotgun.

The male characters in Martyrs are degraded to helpless, passive observers or literal instruments in the hands of women. Their physical strength is not something that bears any political power or stands as criterion for superiority. It echoes the ideas of second-wave feminism that considered Male muscles ‘culturally encouraged, through breeding, diet, and exercise’ and physical strength is nil longer really [politically relevant within ‘civilisation’ (Millet, 2000: 27).

POWER OF THE ANDROGYNOUS GAZE

The look is, in fact, the key of the film’s narrative. The pure, unique gaze recognised in a martyr’s eyes is what enables the martyred individual the ability to glimpse into the ‘after-life’. That independent, not related to anything or anyone aside from nothingness, gaze may be seen as an androgynous gaze freed from all sexuality. That ideal gaze perfectly balancing male and female may be read as the ultimate feminist gaze. Therefore, Anna is the every-woman, and every woman that has ever existed.

Given the social, economic, cultural, ideological but also biological, corporeal suffering that women were doomed to undergo, enables the female form to transform into a higher being, capable of seeing and understanding reality that men will never be able to uncover. Martyrs considers the female form as superior to the male, but also questions why this violence has to exist at all.

Clover reminds us of Thomas Laqueur’s distinction between the “two-sex" and “one-sex” model of sexual difference. Laqueur in his work Making Sex established ‘the “two-sex” or “two-flesh” model, which construes male and female as “opposite” or essentially different from one another (…).’ (Clover, 1992:13) Clover acknowledges that “two-sex” is a ‘relatively modern construction’ that was introduced into shared cultural subconscious in the late eighteenth century, ‘when the female sex was in effect invented as “opposite” to the male’ (Clover, 1992:14) The very core of psychoanalytical analysis of horror, the concepts of penis envy, castration anxiety, phallic woman is “one-sex” thinking, which constitutes sex as inherently male, with ‘woman being “inverted and less perfect, men” possessed of “exactly the same organs but in exactly the wrong places”. Martyrs, that puts the female form on a pedestal with her unique ‘talent’ that makes her more effective in the process of martyrdom, may be read as a horrific satire of the absurd of “one-sex” model. (Clover, 1992:14)

Given the social, economic, cultural, ideological but also biological, corporeal suffering that women were doomed to undergo, enables the female form to transform into a higher being, capable of seeing and understanding reality that men will never be able to uncover. Martyrs considers the female form as superior to the male, but also questions why this violence has to exist at all.

Clover reminds us of Thomas Laqueur’s distinction between the “two-sex" and “one-sex” model of sexual difference. Laqueur in his work Making Sex established ‘the “two-sex” or “two-flesh” model, which construes male and female as “opposite” or essentially different from one another (…).’ (Clover, 1992:13) Clover acknowledges that “two-sex” is a ‘relatively modern construction’ that was introduced into shared cultural subconscious in the late eighteenth century, ‘when the female sex was in effect invented as “opposite” to the male’ (Clover, 1992:14) The very core of psychoanalytical analysis of horror, the concepts of penis envy, castration anxiety, phallic woman is “one-sex” thinking, which constitutes sex as inherently male, with ‘woman being “inverted and less perfect, men” possessed of “exactly the same organs but in exactly the wrong places”. Martyrs, that puts the female form on a pedestal with her unique ‘talent’ that makes her more effective in the process of martyrdom, may be read as a horrific satire of the absurd of “one-sex” model. (Clover, 1992:14)

BIOLOGICAL TORTURE

The biological martyrdom of women also refers to the key elements that formed views on femininity psychoanalysis menstruation, pregnancy, child birth. Shulamith Firestone argues that recognition of women only as bodies, not as rounded individuals, causes their oppression and this can only be overcome by artificial reproduction. By androgenising his heroine, Laugier disturbs the social perception of human reproduction that Firestone (1972:183) insists is the only way to ‘prevent women from suffering pregnancy and childbirth’ and the way ‘to free humanity the tyranny of its biology’. Martyrs distorts this archetypical social order, which adds to the ‘uneasiness’ it reinforces.

Consequently, the references to child birth and ‘monstrous womb’: the imaginary of bathtubs and washing stalls, combined with the chains - symbols of umbilical cords - are omnipresent in the film. The most vivid and memorable allegory to the female womb and labour occurs when Anna discovers the Victim. Her terrorised, distorted body does not reveal the gender. As the metal construction, resembling a medieval chastity belt, covers her eyes and genitals, she is blind and with no control over her reproduction organs. The allegory to the chains that the patriarchal ideology forces on women is vividly clear. Anna carefully washes the Victim and bravely decides to remove the attributes of patriarchal power off of her body. The water in the bathtub fills up with blood and therefore becomes a womb from which new femininity, one without patriarchal constraints, is born. Yet, that femininity is not ready to live, navigate through the world without them. The change was too rapid, not fully conscious, therefore the Victim couldn’t survive in this new order. In order to respond to the dominant reality, a certain amount of subjectivity is required.

Patricia Pisters reminds us that, ‘because dominant categories in reality probably will never disappear, it is important to confront those categories and to deal with them: but process of becoming happen in the same reality: they slip though and in-between the categories’ (Pisters, 2003:111). Becoming-woman is a constant process, that happens on a modular and molecular level and so is feminism. Martyrs implies that distorting the social order itself is not enough, the future female needs to be ready to function in this new world. That brings me back to Firestone and her ideas of artificial reproduction. As logical as her argument is, there is a lingering question about the alternative. As the death of Mademoiselle shows, Anna’s martyrdom, although revealing, did not bring fully successful results. Her suicide may be interpreted as a refusal to accept the fluidity of becoming and therefore as a rejection of societies need to evolve. There are many possible interpretation of the film’s ending, but the fact that Mademoiselle denied her knowledge to other members of the group is telling. She declined the possible effect of that knowledge onto wider society. Yet the process of becoming is not broken, it IS happening and is being shared and experienced by every viewer ‘touched’ by Martyrs.

Laugier’s film is undoubtedly a unique text which deeply challenges social preconceptions about gender. Despite the fact it was released 10 years ago, Martyrs still gets under the audiences skin by exhibiting the bare flesh of femininity and process of pure becoming though the most cathartic film genre. But this is not a horror that, through blood and suffering, leads to ultimate cleansing. It made us feel dirty for being just a passive cog in a patriarchal machine. It is a feminist film that asks questions without pretending its for the answers, in the same way as Ken Loch approaches social issues. It does not provide a readily available solution but helps us to see what is wrong. Martyrs debunks gender as a social construct in a civilisation whose values need to be redefined.

by Paulina

Consequently, the references to child birth and ‘monstrous womb’: the imaginary of bathtubs and washing stalls, combined with the chains - symbols of umbilical cords - are omnipresent in the film. The most vivid and memorable allegory to the female womb and labour occurs when Anna discovers the Victim. Her terrorised, distorted body does not reveal the gender. As the metal construction, resembling a medieval chastity belt, covers her eyes and genitals, she is blind and with no control over her reproduction organs. The allegory to the chains that the patriarchal ideology forces on women is vividly clear. Anna carefully washes the Victim and bravely decides to remove the attributes of patriarchal power off of her body. The water in the bathtub fills up with blood and therefore becomes a womb from which new femininity, one without patriarchal constraints, is born. Yet, that femininity is not ready to live, navigate through the world without them. The change was too rapid, not fully conscious, therefore the Victim couldn’t survive in this new order. In order to respond to the dominant reality, a certain amount of subjectivity is required.

Patricia Pisters reminds us that, ‘because dominant categories in reality probably will never disappear, it is important to confront those categories and to deal with them: but process of becoming happen in the same reality: they slip though and in-between the categories’ (Pisters, 2003:111). Becoming-woman is a constant process, that happens on a modular and molecular level and so is feminism. Martyrs implies that distorting the social order itself is not enough, the future female needs to be ready to function in this new world. That brings me back to Firestone and her ideas of artificial reproduction. As logical as her argument is, there is a lingering question about the alternative. As the death of Mademoiselle shows, Anna’s martyrdom, although revealing, did not bring fully successful results. Her suicide may be interpreted as a refusal to accept the fluidity of becoming and therefore as a rejection of societies need to evolve. There are many possible interpretation of the film’s ending, but the fact that Mademoiselle denied her knowledge to other members of the group is telling. She declined the possible effect of that knowledge onto wider society. Yet the process of becoming is not broken, it IS happening and is being shared and experienced by every viewer ‘touched’ by Martyrs.

Laugier’s film is undoubtedly a unique text which deeply challenges social preconceptions about gender. Despite the fact it was released 10 years ago, Martyrs still gets under the audiences skin by exhibiting the bare flesh of femininity and process of pure becoming though the most cathartic film genre. But this is not a horror that, through blood and suffering, leads to ultimate cleansing. It made us feel dirty for being just a passive cog in a patriarchal machine. It is a feminist film that asks questions without pretending its for the answers, in the same way as Ken Loch approaches social issues. It does not provide a readily available solution but helps us to see what is wrong. Martyrs debunks gender as a social construct in a civilisation whose values need to be redefined.

by Paulina

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Buchanan, I. (2002). Deleuze and Feminist Theory. Edinburgh : Edinburgh University Press

Clover, C. J. (1992). Men, women, and chain saws: Gender in the modern horror film. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (2004). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Continuum.

Firestone, S. (1971). The dialectic of sex: The case for feminist revolution. New York: Bantam Books

Green, A. (2011) The French Horror Film Martyrs and the Destruction, Defilement, and Neutering of the Female Form. Journal of Popular Film & Television

Millett, K. (2000). Sexual politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual and other pleasures. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan.

Pisrters, P. (2003) The Matrix of Visual Culture – Working with Deleuze in Film Theory. Stanford: Stanford University Press

Wood, R. (1986) Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan.. Columbia University Press, 1986

Clover, C. J. (1992). Men, women, and chain saws: Gender in the modern horror film. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (2004). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Continuum.

Firestone, S. (1971). The dialectic of sex: The case for feminist revolution. New York: Bantam Books

Green, A. (2011) The French Horror Film Martyrs and the Destruction, Defilement, and Neutering of the Female Form. Journal of Popular Film & Television

Millett, K. (2000). Sexual politics. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual and other pleasures. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan.

Pisrters, P. (2003) The Matrix of Visual Culture – Working with Deleuze in Film Theory. Stanford: Stanford University Press

Wood, R. (1986) Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan.. Columbia University Press, 1986