Paulina's Gore Corner: Episode 5 - Martyrs (2008) 10/08/18

In last week’s instalment of my Gore Corner I continued my investigation of the distinctive New French Extremism by looking closely at Marina de Van’s In My Skin (Dans ma peau) (2002). The film is a graphic and disturbing depiction of desire to connect the mind with the body, manifested through the heroine’s obsession with self mutilation. In My Skin is a compelling study that illustrates the tendency of Western culture to alienate our psyche from the body, It explores deeply Deleuze’s notion of ‘flesh’ as well as ‘the body-without-organs’ coined by Artaud that ‘suggests the “true”condition of the human body if freed from punishments of a repressive God’ (Powell, 2005: 211).

De Van’s film, with its explicit representation of violence (interestingly it is self-violence in this case) and readiness to break the socio-cultural taboos (self-cannibalism), embodies the main characteristics of New French Extremism and undoubtedly is a movement defining piece. Notwithstanding, Pascal Laugier's 2008 French horror film Martyrs goes even further with its aspiration to shock, repulse and ultimately liberate the audience from the bodily limitations through unthinkable suffering.

Martyrs premiered at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival, and was ominous for its first audiences to such a degree that incidents of viewers passing out and vomiting were widely reported (Green, 2011: 21). Indeed, the depiction of violence is truly sickening in Laugier’s film and undisputedly rivals the gore of slasher film such as Hostel (2005), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), House of 1000 Corpses (2003) or Saw (2004). But there’s something more about Martyrs that doesn’t allow the viewers to forget about it for days. It’s the feeling of immense emptiness and numb darkness it evokes. What the film does successfully is inflect humans interiority with something that we escape from the moment our subconscious is formed, something beyond kitchen nihilism and its radical scepticism: the nothingness, the void, the primal blackness . Martyrs reminds us of this eternal nothingness, the one that exists before we are born and after we die. Therefore, the film courageously addresses the illusion that Western cultures feeds itself with while trying to escape from thoughts of the void. Martyrs brutally exposes these lies and confronts the viewer with the horrors of contemporary Western civilisation manifested in the film’s universe. In an interview with Virginie Sélavy, Pascal Laugier (2009) revealed the genesis of Martyrs and the main motifs that were in his focus:

The film is a personal reaction to the darkness of our world. And I like the paradox within horror film: take the worst of the human condition and transform it into art, into beauty. It’s the only genre that offers this kind of dialectic and I have always found this idea very moving – to create emotion with the saddest, most depressing things in existence. I’ve always felt that horror was a melancholy genre.

Romanticising violence is one the defining characterise of New French Extremism, with Pola X (1999) being possibly the clearest example. Martyrs’ violence, despite being overwhelming, graphic, and extensive, is also intimately erotic. Moreover, it doesn’t provide catharsis or the peculiar pleasure of following well known narrative mechanisms as most horrors do. Instead, it destroys all familiar schemes as it takes aim at what holds Western civilisation together: capitalistic values, the inability to confront the shameful past and guilt it creates, and politics organised in favour of those in power. Martyrs is not a film designed for mindless escapism. In contrast, it doesn’t allow the viewer to relax even for split second, the tension is constant, omnipresent, and multilayered. It is not based on cheap generic techniques such as jump scares or a high dosage of CGI effects combined with thoughtless bloodshed. The critics who consider Martyrs as ‘kind of all-torture-all-the-time movie’ ( Ebert, 2016) choose to ignore its ambitious and vastly successful attempt to portray the critical state of not only French, but Western society as a whole.

While aspiring to articulate and analyse the sensations and impression Martyrs provokes, once again I found the tools provided by a psychoanalytical approach to film studies - the concepts of Oedipal triangulation, the uncanny, and castration anxiety - not efficient enough as these disregard the ‘aesthetic of sensation’. In my struggle with the limitations of psychoanalytical readings, I re-discovered Deleuze. As in the case of In My Skin, his notion of flesh, Affection-Image, Becoming, Time-Image and Schizoanalysis become extremely helpful while looking at this type of highly sensualised violence.

Schizoanalysis has been grounded in the work of unconventional psychoanalyst William Reich in his 1933 book, The Mass Psychology of Fascism in which he explores the psychology of the masses and proposes that psycho-somatic structures of society are what ‘make fascism possible at the outset’ (A.T. Kingsmith, 2016). Its definition was evolving through the philosophic research of Nietzsche, Marx, and Freud, as well as Deleuze and Guattari. All of these thinkers, however, would see schizoanalysis as a revolutionary political process that seeks to expand upon Reich’s materialist-psychiatric. The schizoanalytical approach gives deeper meaning and justification to the Donato Totaro’s analysis in which he views Martyrs as ‘evoking France’s cinematic and historical past’ including the guilt and shame inflicted by close collaboration of Vichy government with Nazi Germany and France’s failures during II World War.

The traumas so profoundly inflicted in a nation’s soul cannot be read by the mind. Therefore, the film needs to provoke the body to respond. Following this direction, Pascal Laughier can be regarded as the director of Deleuze’s impulse-image. The impulse-image, full of symptoms and fetishes, is positioned ‘between the affection image (which is no longer) and action-image (which is not yet)’ and Deleuze sees in them the ‘perverse modes of behaviour’ such as sadomasochism or cannibalism (Pisters, 2003:81). The uncontrollable impulses that ‘degrade’ human to animal-like state: the tortured woman obsessively scratching herself as she hallucinates flies and spiders, or Esther inability to control the appetite for her own flesh.

Deleuze’s approach to schizoanalysis draws on the clinical definition of schizophrenia as proposed by Jean Laplanche and J.B Pontalis:

The pathological condition reveals ‘incoherence of thought, action, affectivity’ It involves ‘discordance, dissociation, disintegration’, accompanied by detachment from reality in ‘a turning in upon the self and predominance of a delusional mental life given over to the production of phantasies’ (autism) and ultimately ‘intellectual and affective “deterioration”’ (Powell, 2005:19)

Deleuze and Guattari expand on this notion by regarding schizoanalysis as operating at ‘the outside of psychoanalysis itself which can only be revealed through an internal reversal of its analytical categories’. Consequently, the ‘psychos’, in Deleuze’s and Guattari’s view, are the ‘experimental artists such as modernists and their precursor’ (Powell, 2005:21). Consequently, the directors creating outside of Hollywood producing independent, experimental films, including Pascal Laugier, can be considered as schizos. The thinkers describe the figure of schizo as :

‘A free man, irresponsible, solitary and joyous, finally able to say. And do something simple in his own name, without asking permission, a desire lacking nothing, a flux that overcomes barriers and codes, a name that no longer designates any ego whatever’ (Powell, 2005:21).

Indeed, Martyrs feels like the product of a troubled mind. Not just the filmmaker’s mind but the collective, social mind. It brings me back to Reich’s study of mass psychology of fascism: it is not the ‘schizophrenic’ Laugier who produced this utterly depressing vision of humankind. It is Western society, the masses, that desire and created it.

The film starts with a young, horribly abused girl escaping from an abandoned factory where she was kept by her perpetrators. The image clearly evokes the famous picture that became the symbol of Vietnam: a little Vietnamese child running from death down an apocalyptic road. As the girl, Lucie, is unable to communicate with anyone, she is transferred into psychiatric institution where she befriends Anna. The girls become and stay inseparable for another 15 years when we meet them again in even more dramatic circumstances. Lucie brutally disturbs the breakfast of a regular, wealthy family by breaking in and slaughtering them all. As she phones Anna, asking for help with cleaning the murder scene, we find out that the family were Lucie’s abusers who traumatised and tortured her and left scars on her body and mind. The domestic space is befouled with the blood of its inhabitants. Consequently, film changes direction and becomes a bloodcurdling study of Anna’s martyrdom. The camera lingers on Anna’s beaten up body, circulating around her in hand held, shaky movements. When the woman internally lets go of any remaining ego and immerses herself in her anguish, the pace of the film changes, it slows down. Deleuze distinguishes ‘internal time of the spirit from historical one’. Therefore, in Martyrs the ‘dual nature (…) of physical and metaphysical experience are expressed through cinematography and powerful performance by Morjana Alaoui.'

De Van’s film, with its explicit representation of violence (interestingly it is self-violence in this case) and readiness to break the socio-cultural taboos (self-cannibalism), embodies the main characteristics of New French Extremism and undoubtedly is a movement defining piece. Notwithstanding, Pascal Laugier's 2008 French horror film Martyrs goes even further with its aspiration to shock, repulse and ultimately liberate the audience from the bodily limitations through unthinkable suffering.

Martyrs premiered at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival, and was ominous for its first audiences to such a degree that incidents of viewers passing out and vomiting were widely reported (Green, 2011: 21). Indeed, the depiction of violence is truly sickening in Laugier’s film and undisputedly rivals the gore of slasher film such as Hostel (2005), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), House of 1000 Corpses (2003) or Saw (2004). But there’s something more about Martyrs that doesn’t allow the viewers to forget about it for days. It’s the feeling of immense emptiness and numb darkness it evokes. What the film does successfully is inflect humans interiority with something that we escape from the moment our subconscious is formed, something beyond kitchen nihilism and its radical scepticism: the nothingness, the void, the primal blackness . Martyrs reminds us of this eternal nothingness, the one that exists before we are born and after we die. Therefore, the film courageously addresses the illusion that Western cultures feeds itself with while trying to escape from thoughts of the void. Martyrs brutally exposes these lies and confronts the viewer with the horrors of contemporary Western civilisation manifested in the film’s universe. In an interview with Virginie Sélavy, Pascal Laugier (2009) revealed the genesis of Martyrs and the main motifs that were in his focus:

The film is a personal reaction to the darkness of our world. And I like the paradox within horror film: take the worst of the human condition and transform it into art, into beauty. It’s the only genre that offers this kind of dialectic and I have always found this idea very moving – to create emotion with the saddest, most depressing things in existence. I’ve always felt that horror was a melancholy genre.

Romanticising violence is one the defining characterise of New French Extremism, with Pola X (1999) being possibly the clearest example. Martyrs’ violence, despite being overwhelming, graphic, and extensive, is also intimately erotic. Moreover, it doesn’t provide catharsis or the peculiar pleasure of following well known narrative mechanisms as most horrors do. Instead, it destroys all familiar schemes as it takes aim at what holds Western civilisation together: capitalistic values, the inability to confront the shameful past and guilt it creates, and politics organised in favour of those in power. Martyrs is not a film designed for mindless escapism. In contrast, it doesn’t allow the viewer to relax even for split second, the tension is constant, omnipresent, and multilayered. It is not based on cheap generic techniques such as jump scares or a high dosage of CGI effects combined with thoughtless bloodshed. The critics who consider Martyrs as ‘kind of all-torture-all-the-time movie’ ( Ebert, 2016) choose to ignore its ambitious and vastly successful attempt to portray the critical state of not only French, but Western society as a whole.

While aspiring to articulate and analyse the sensations and impression Martyrs provokes, once again I found the tools provided by a psychoanalytical approach to film studies - the concepts of Oedipal triangulation, the uncanny, and castration anxiety - not efficient enough as these disregard the ‘aesthetic of sensation’. In my struggle with the limitations of psychoanalytical readings, I re-discovered Deleuze. As in the case of In My Skin, his notion of flesh, Affection-Image, Becoming, Time-Image and Schizoanalysis become extremely helpful while looking at this type of highly sensualised violence.

Schizoanalysis has been grounded in the work of unconventional psychoanalyst William Reich in his 1933 book, The Mass Psychology of Fascism in which he explores the psychology of the masses and proposes that psycho-somatic structures of society are what ‘make fascism possible at the outset’ (A.T. Kingsmith, 2016). Its definition was evolving through the philosophic research of Nietzsche, Marx, and Freud, as well as Deleuze and Guattari. All of these thinkers, however, would see schizoanalysis as a revolutionary political process that seeks to expand upon Reich’s materialist-psychiatric. The schizoanalytical approach gives deeper meaning and justification to the Donato Totaro’s analysis in which he views Martyrs as ‘evoking France’s cinematic and historical past’ including the guilt and shame inflicted by close collaboration of Vichy government with Nazi Germany and France’s failures during II World War.

The traumas so profoundly inflicted in a nation’s soul cannot be read by the mind. Therefore, the film needs to provoke the body to respond. Following this direction, Pascal Laughier can be regarded as the director of Deleuze’s impulse-image. The impulse-image, full of symptoms and fetishes, is positioned ‘between the affection image (which is no longer) and action-image (which is not yet)’ and Deleuze sees in them the ‘perverse modes of behaviour’ such as sadomasochism or cannibalism (Pisters, 2003:81). The uncontrollable impulses that ‘degrade’ human to animal-like state: the tortured woman obsessively scratching herself as she hallucinates flies and spiders, or Esther inability to control the appetite for her own flesh.

Deleuze’s approach to schizoanalysis draws on the clinical definition of schizophrenia as proposed by Jean Laplanche and J.B Pontalis:

The pathological condition reveals ‘incoherence of thought, action, affectivity’ It involves ‘discordance, dissociation, disintegration’, accompanied by detachment from reality in ‘a turning in upon the self and predominance of a delusional mental life given over to the production of phantasies’ (autism) and ultimately ‘intellectual and affective “deterioration”’ (Powell, 2005:19)

Deleuze and Guattari expand on this notion by regarding schizoanalysis as operating at ‘the outside of psychoanalysis itself which can only be revealed through an internal reversal of its analytical categories’. Consequently, the ‘psychos’, in Deleuze’s and Guattari’s view, are the ‘experimental artists such as modernists and their precursor’ (Powell, 2005:21). Consequently, the directors creating outside of Hollywood producing independent, experimental films, including Pascal Laugier, can be considered as schizos. The thinkers describe the figure of schizo as :

‘A free man, irresponsible, solitary and joyous, finally able to say. And do something simple in his own name, without asking permission, a desire lacking nothing, a flux that overcomes barriers and codes, a name that no longer designates any ego whatever’ (Powell, 2005:21).

Indeed, Martyrs feels like the product of a troubled mind. Not just the filmmaker’s mind but the collective, social mind. It brings me back to Reich’s study of mass psychology of fascism: it is not the ‘schizophrenic’ Laugier who produced this utterly depressing vision of humankind. It is Western society, the masses, that desire and created it.

The film starts with a young, horribly abused girl escaping from an abandoned factory where she was kept by her perpetrators. The image clearly evokes the famous picture that became the symbol of Vietnam: a little Vietnamese child running from death down an apocalyptic road. As the girl, Lucie, is unable to communicate with anyone, she is transferred into psychiatric institution where she befriends Anna. The girls become and stay inseparable for another 15 years when we meet them again in even more dramatic circumstances. Lucie brutally disturbs the breakfast of a regular, wealthy family by breaking in and slaughtering them all. As she phones Anna, asking for help with cleaning the murder scene, we find out that the family were Lucie’s abusers who traumatised and tortured her and left scars on her body and mind. The domestic space is befouled with the blood of its inhabitants. Consequently, film changes direction and becomes a bloodcurdling study of Anna’s martyrdom. The camera lingers on Anna’s beaten up body, circulating around her in hand held, shaky movements. When the woman internally lets go of any remaining ego and immerses herself in her anguish, the pace of the film changes, it slows down. Deleuze distinguishes ‘internal time of the spirit from historical one’. Therefore, in Martyrs the ‘dual nature (…) of physical and metaphysical experience are expressed through cinematography and powerful performance by Morjana Alaoui.'

Until this point the depiction of violence is graphic but not so controversial. Patricia Pisters noted the representation of violence on screen is treated dually. The first approach sees violence as immoral as well as causing and reinforcing negative social behaviour. The other one barely notices violence and inflicts it into the film’s universe as a natural ingredient. Martyrs, in contrast sees the poetry of violence as an artistic expression without judging the violence itself through the eyes of a socially constructed God. Deleuze claims that ‘there is no Good or Evil in Nature in general, but there is good and sadness, useful and harmful, for each existing modes’ (Pisters, 86).

Martyrs illustrates this view by breaking the narrative structure and drastically changing the premise of the story. The film starts as the revenge slasher horror with viewer identifying with Lucie and justifying her brutal murder. That certainty, however, is questioned while Lucie’s mental state worsens. We are not convinced anymore if Lucie took the lives of the right people. The situation gets complicated when Lucie’s guilt manifests itself through a Freudian monster of the id, the Creature that haunts the woman and inflicts serious physical injuries and eventually causes Lucie to kill herself. In this moment, the story takes an unexpected and drastic twist that evokes Hitchcock’s murder of his heroine in the first part of Psycho that truly traumatised the viewers. After Lucie’s death, it is her ultimately devoted friend Anna who becomes the film’s focus. While she tries to escape the murder scene, she discovers the basement in which a battered and tortured woman is kept. From this moment, the violence that will unfold in front of our eyes will be beyond judgement. In another selfless, desperate attempt to help a human being, Anna is caught by the sinister organisation lead by Mademoiselle (Catherine Bégin). The group catches and tortures young woman to the point when, through intense suffering, they will be able to experience a transcendental vision which will reveal what is waiting for us in the afterlife.

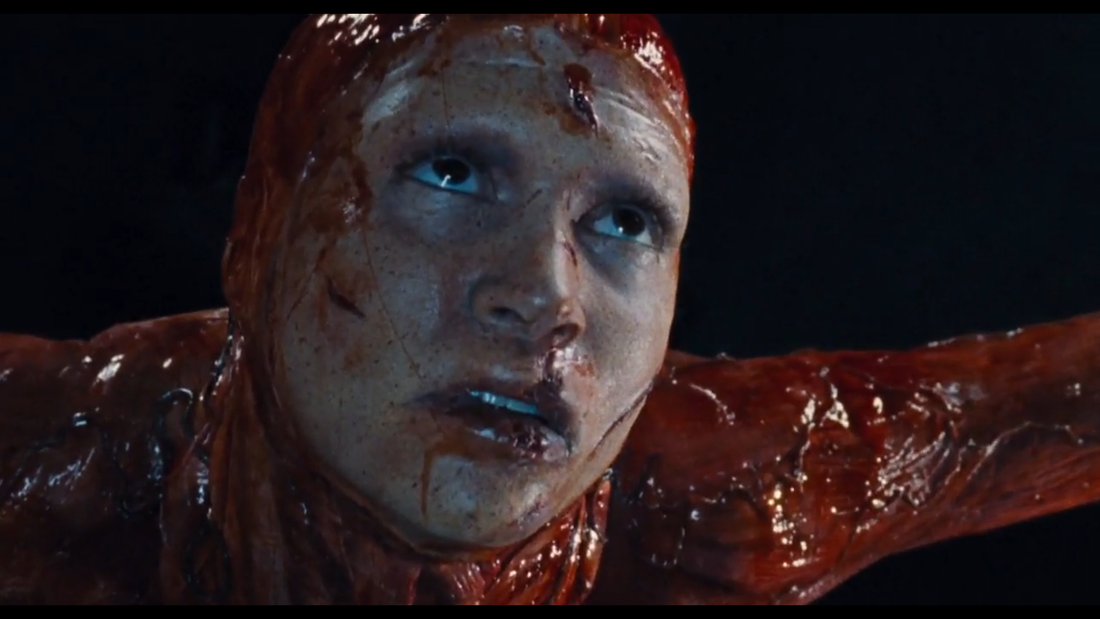

The most traumatic image in the film is that of Anna, resembling a laboratory-created Christ, after being skinned alive. Her martyrdom transformed her into an archaic body-without-organs, ‘mutated beyond fixed gender oppositions’ (Powell, 2005: 79) exhibiting the flesh: the deepest hidden ‘I’. The ‘true’ body that is replaced by the dominant system’ through an ‘organised body on which God can exercise his judgement’ (Powell, 2005: 78). Interestingly, the fact that Anna’s face wasn’t skinned serves as an alluring analogy to earlier French horror that evokes France’s war traumas - Les Yeux sans Visage (Eyes Without A Face (1960)) - in which Christiane was robbed of the skin from her face. According to Anna Powell, ‘skin is the most sensitive bodily organ and the facial features it covers are most intimately connected to our social self of selfhood (…)’ (2005:147). Would that be a hint provided by film for the audience that the martyrdom Anna endured was not full, not real? Would that mean that she lied to Mademoiselle in order to stop the vicious cycle of violence? That may indicate that the real martyr was in fact Mademoiselle, who died to keep alive the organisation she dedicated all her life for. This is, however, only one of many possible interpretations of film’s ambiguous ending. There were rumours that the real reason for Martyrs’ enigmatic conclusion was the lack of funds and time to finish the film as initially planned. Whatever the cause, the ending provides an invitation to further debate, and moves the real meaning of this disturbing film from destination to the journey that the viewer experiences.

This article only slightly touches the motifs, symbols, and allegories hidden in Martyrs. There is still so much to say about the racial and gender issues of the film but my main aim was to demonstrate the usefulnesses of Deleuze’s thought in order to decrypt the films of New Film Extremism. Anna Powell acknowledges that ‘Deleuze’s cinema is not a purely visual, spectacular experience. It embraces the flux of corporeal sensation and sensory perception in the ‘machine’ connection of the embodied spectator with the body of the text’ (2005:4). The films that explore taboos and try to break mental barriers so deeply rooted in the individual and shared subconsciousness, cannot refer to psyche as it won’t be able to digest it. It is the body that these films need to be experienced through and therefore, they need to be read through the body: both the body of the film, and the sensation it invokes in the spectator’s body. It is striking how the final gaze of Anna, the gaze of a martyr resembles the one of the ideal viewer, lost utterly and totally in the film.

In next week's instalments of my Gore Corner I am going to continue using Deleuze’s ‘neo-aesthetic’ philosophy to explore cinematic extremes in Gaspar Noé’s captivating horror/drama Enter The Void (2009). As I conduct on-going research on New French Extremism and find my haptic approaches surprisingly alienated in relation to extremist film, I would welcome feedback and thoughts from the readers. Please, feel free to leave a comment and express your opinion!

by Paulina

Martyrs illustrates this view by breaking the narrative structure and drastically changing the premise of the story. The film starts as the revenge slasher horror with viewer identifying with Lucie and justifying her brutal murder. That certainty, however, is questioned while Lucie’s mental state worsens. We are not convinced anymore if Lucie took the lives of the right people. The situation gets complicated when Lucie’s guilt manifests itself through a Freudian monster of the id, the Creature that haunts the woman and inflicts serious physical injuries and eventually causes Lucie to kill herself. In this moment, the story takes an unexpected and drastic twist that evokes Hitchcock’s murder of his heroine in the first part of Psycho that truly traumatised the viewers. After Lucie’s death, it is her ultimately devoted friend Anna who becomes the film’s focus. While she tries to escape the murder scene, she discovers the basement in which a battered and tortured woman is kept. From this moment, the violence that will unfold in front of our eyes will be beyond judgement. In another selfless, desperate attempt to help a human being, Anna is caught by the sinister organisation lead by Mademoiselle (Catherine Bégin). The group catches and tortures young woman to the point when, through intense suffering, they will be able to experience a transcendental vision which will reveal what is waiting for us in the afterlife.

The most traumatic image in the film is that of Anna, resembling a laboratory-created Christ, after being skinned alive. Her martyrdom transformed her into an archaic body-without-organs, ‘mutated beyond fixed gender oppositions’ (Powell, 2005: 79) exhibiting the flesh: the deepest hidden ‘I’. The ‘true’ body that is replaced by the dominant system’ through an ‘organised body on which God can exercise his judgement’ (Powell, 2005: 78). Interestingly, the fact that Anna’s face wasn’t skinned serves as an alluring analogy to earlier French horror that evokes France’s war traumas - Les Yeux sans Visage (Eyes Without A Face (1960)) - in which Christiane was robbed of the skin from her face. According to Anna Powell, ‘skin is the most sensitive bodily organ and the facial features it covers are most intimately connected to our social self of selfhood (…)’ (2005:147). Would that be a hint provided by film for the audience that the martyrdom Anna endured was not full, not real? Would that mean that she lied to Mademoiselle in order to stop the vicious cycle of violence? That may indicate that the real martyr was in fact Mademoiselle, who died to keep alive the organisation she dedicated all her life for. This is, however, only one of many possible interpretations of film’s ambiguous ending. There were rumours that the real reason for Martyrs’ enigmatic conclusion was the lack of funds and time to finish the film as initially planned. Whatever the cause, the ending provides an invitation to further debate, and moves the real meaning of this disturbing film from destination to the journey that the viewer experiences.

This article only slightly touches the motifs, symbols, and allegories hidden in Martyrs. There is still so much to say about the racial and gender issues of the film but my main aim was to demonstrate the usefulnesses of Deleuze’s thought in order to decrypt the films of New Film Extremism. Anna Powell acknowledges that ‘Deleuze’s cinema is not a purely visual, spectacular experience. It embraces the flux of corporeal sensation and sensory perception in the ‘machine’ connection of the embodied spectator with the body of the text’ (2005:4). The films that explore taboos and try to break mental barriers so deeply rooted in the individual and shared subconsciousness, cannot refer to psyche as it won’t be able to digest it. It is the body that these films need to be experienced through and therefore, they need to be read through the body: both the body of the film, and the sensation it invokes in the spectator’s body. It is striking how the final gaze of Anna, the gaze of a martyr resembles the one of the ideal viewer, lost utterly and totally in the film.

In next week's instalments of my Gore Corner I am going to continue using Deleuze’s ‘neo-aesthetic’ philosophy to explore cinematic extremes in Gaspar Noé’s captivating horror/drama Enter The Void (2009). As I conduct on-going research on New French Extremism and find my haptic approaches surprisingly alienated in relation to extremist film, I would welcome feedback and thoughts from the readers. Please, feel free to leave a comment and express your opinion!

by Paulina

Bibliography

Ebert, R. Martyrs, 2016 [https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/martyrs-2016]

Kingsmith, A.T an introduction to schizoanalysis, 2016. 3AM Magazine [https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/an-introduction-to-schizoanalysis/]

Pisters, P. The Matrix of Visual Culture, 2005, Standford, California: Standford University Press

Powell, A. Deleuze and Horror Film, 2005, Ediburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd.

Sélavy, V. MARTYRS: INTERVIEW WITH PASCAL LAUGIER, 2009 [http://www.electricsheepmagazine.co.uk/features/2009/05/02/martyrs-interview-with-pascal-laugier/]

Totaro, D. Martyrs: Evoking France’s Cinematic and Historical Past, 2009, OFFSCREEN [http://offscreen.com/view/martyrs_historical]

Kingsmith, A.T an introduction to schizoanalysis, 2016. 3AM Magazine [https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/an-introduction-to-schizoanalysis/]

Pisters, P. The Matrix of Visual Culture, 2005, Standford, California: Standford University Press

Powell, A. Deleuze and Horror Film, 2005, Ediburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd.

Sélavy, V. MARTYRS: INTERVIEW WITH PASCAL LAUGIER, 2009 [http://www.electricsheepmagazine.co.uk/features/2009/05/02/martyrs-interview-with-pascal-laugier/]

Totaro, D. Martyrs: Evoking France’s Cinematic and Historical Past, 2009, OFFSCREEN [http://offscreen.com/view/martyrs_historical]