Paulina's Gore Corner Episode 4: In My Skin 03/08/18

Last week I talked briefly about the genesis and characteristics of films that have been created in the spirit of New French Extremism. The movement is not restricted specifically to the horror genre, however the distinguished attention that Extremist films pay to the broadly defined concept of body often produces material that balances on the verge of body horror or cine du corpse which, as Tim Palmer noted, ‘conveys forcibly its provocative materials, fraught on-screen treatments of the body that evoke new levels of perceptual engagement from the viewer’ (Palmer, 2007:180). In My Skin (2002), Marina de Van’s movement-defining psychological horror, is a perfect example of using transgression in order to represent the body, as the film situates it body in its centre. It calls for a freeing of the body from restrictions and boundaries set up by the mind, and to let it exist, to feel and perceive the world on its own. De Van’s film invites - or even demands - to explore ‘cinema’s tactility’ and appreciate it ‘as an intimate experience and of our relationship with cinema as a close connection, rather than a distant experience of observation’. (Barker, 2009, 2).

In My Skin tells the story of a successful young woman, Esther, who becomes obsessed with literally exploring her leg injury. As she fails to notice the pain after what appears to be an inconsequential accident at a party, she starts touching, irritating and eventually digging deeper and deeper into her flesh. The mixture of sadomasochistic pleasure and guilt consequently prevents Esther to carry on with her love and work life. At first glance, the unexceptional heroine appears to be in a rewarding moment of her life with a great job in a company that specialises in the customer surveys. Esther is hard working, professional and striving for the promotion that will bring her financial security as she is just about to move in with her boyfriend. Soon, the other side of Esther comes out, her bodily, therefore animal-like side as she gets caught up in maniacal acts of self-destruction.

The film undoubtedly seeks to be approached through its body. Yet, there is more than just the cinematic body that needs to be discussed in case of In My Skin. The film can regraded as a national body, with Esther’s - and de Van’s - body resembling France. It emphasises France’s deeply rooted, unconcluded traumas and demons reaching as far back as it’s colonial past. Additionally, she is the body of the everyman at the dawn of the new millennium acting as a catalyst of his anxieties and diseases.

Nevertheless, the body of the viewer, inextricably connected to the one of the film, cannot be omitted. The audience’s bodily response to the film is what makes it so gripping and powerful. The uneasiness that overcomes us and stays for hours after the screening. The film’s transformative potential comes from exposing the viewer to what is always so carefully hidden, covered in a tight mask of the skin, the real essence of our existence: the flesh. The notion of flesh is extremely helpful for interpreting the films of New French Extremism and de Van, a former philosophy student, distinctly investigates the matter in her film. In this article I am going to approach In My Skin by engaging the concepts of meat and flesh formulated by Deleuze and Merleau-Ponty.

Firstly, I shall elaborate on the body of the film and simultaneously, on the embodied spectatorship it provides. Gilian Deleuze described film as a ‘turning crystal’ which, as he explained,

‘Has two definite sides which are not be confused. For the confusion of the real and the imaginary is a simple error of fact, and does not affect their discernibility: the confusion is produced solely in someone’s head. But indiscernibility constitutes an objective illusion, it does not suppress the distinction between the two sides, but makes it unattributable, each side taking the other’s role in relation which me must describe as reciprocal presupposition or reversability’ (Barker, 2009:7).

I apologise for the length and density of the above quote but I find the notion of crystal-image crucial in order to approach tactility and Deleuze, known for his poetic but complicated style, is especially difficult to paraphrase without losing the essence. The main point the philosopher is calling into question is that quality of cinema that makes us lose ourselves in the film and causes the boundaries between ‘character identification and objective observation’ to collapse. It is important in relation to In My Skin as the experience that film provides is particularly embodied. It constitutes us, the audience, in Esther’s position and forces us to dig a hole into our own flesh.

The initial disguise is being replaced by the same uncanny curiosity and pleasure that drives Esther to auto-mutilation. The film leaves us weirdly satisfied as it provokes the body to clear our psyche.

In My Skin emphasises its main motif and goal (to uncover what always has been covered) at the very beginning. The film opens with a montage of split-screen still shots of urban landscapes, Ester’s everyday day environment. By juxtaposing Positive and Negative images the film gives away its demand to break the boundaries of ever-worn protection, to take off its skin. It is a forceful invitation that is directed equally towards Esther and the viewer.

In My Skin doesn’t allow us to look away during most comfortable shots. We are not even able to blink as the film doesn’t cut when Easter cuts off her skin with a knife and eats her own flesh. The camera observes the heroine in continuous, lengthy close ups when she pokes the injury under her bandage and the screen fills up with blood and pus.

In My Skin tells the story of a successful young woman, Esther, who becomes obsessed with literally exploring her leg injury. As she fails to notice the pain after what appears to be an inconsequential accident at a party, she starts touching, irritating and eventually digging deeper and deeper into her flesh. The mixture of sadomasochistic pleasure and guilt consequently prevents Esther to carry on with her love and work life. At first glance, the unexceptional heroine appears to be in a rewarding moment of her life with a great job in a company that specialises in the customer surveys. Esther is hard working, professional and striving for the promotion that will bring her financial security as she is just about to move in with her boyfriend. Soon, the other side of Esther comes out, her bodily, therefore animal-like side as she gets caught up in maniacal acts of self-destruction.

The film undoubtedly seeks to be approached through its body. Yet, there is more than just the cinematic body that needs to be discussed in case of In My Skin. The film can regraded as a national body, with Esther’s - and de Van’s - body resembling France. It emphasises France’s deeply rooted, unconcluded traumas and demons reaching as far back as it’s colonial past. Additionally, she is the body of the everyman at the dawn of the new millennium acting as a catalyst of his anxieties and diseases.

Nevertheless, the body of the viewer, inextricably connected to the one of the film, cannot be omitted. The audience’s bodily response to the film is what makes it so gripping and powerful. The uneasiness that overcomes us and stays for hours after the screening. The film’s transformative potential comes from exposing the viewer to what is always so carefully hidden, covered in a tight mask of the skin, the real essence of our existence: the flesh. The notion of flesh is extremely helpful for interpreting the films of New French Extremism and de Van, a former philosophy student, distinctly investigates the matter in her film. In this article I am going to approach In My Skin by engaging the concepts of meat and flesh formulated by Deleuze and Merleau-Ponty.

Firstly, I shall elaborate on the body of the film and simultaneously, on the embodied spectatorship it provides. Gilian Deleuze described film as a ‘turning crystal’ which, as he explained,

‘Has two definite sides which are not be confused. For the confusion of the real and the imaginary is a simple error of fact, and does not affect their discernibility: the confusion is produced solely in someone’s head. But indiscernibility constitutes an objective illusion, it does not suppress the distinction between the two sides, but makes it unattributable, each side taking the other’s role in relation which me must describe as reciprocal presupposition or reversability’ (Barker, 2009:7).

I apologise for the length and density of the above quote but I find the notion of crystal-image crucial in order to approach tactility and Deleuze, known for his poetic but complicated style, is especially difficult to paraphrase without losing the essence. The main point the philosopher is calling into question is that quality of cinema that makes us lose ourselves in the film and causes the boundaries between ‘character identification and objective observation’ to collapse. It is important in relation to In My Skin as the experience that film provides is particularly embodied. It constitutes us, the audience, in Esther’s position and forces us to dig a hole into our own flesh.

The initial disguise is being replaced by the same uncanny curiosity and pleasure that drives Esther to auto-mutilation. The film leaves us weirdly satisfied as it provokes the body to clear our psyche.

In My Skin emphasises its main motif and goal (to uncover what always has been covered) at the very beginning. The film opens with a montage of split-screen still shots of urban landscapes, Ester’s everyday day environment. By juxtaposing Positive and Negative images the film gives away its demand to break the boundaries of ever-worn protection, to take off its skin. It is a forceful invitation that is directed equally towards Esther and the viewer.

In My Skin doesn’t allow us to look away during most comfortable shots. We are not even able to blink as the film doesn’t cut when Easter cuts off her skin with a knife and eats her own flesh. The camera observes the heroine in continuous, lengthy close ups when she pokes the injury under her bandage and the screen fills up with blood and pus.

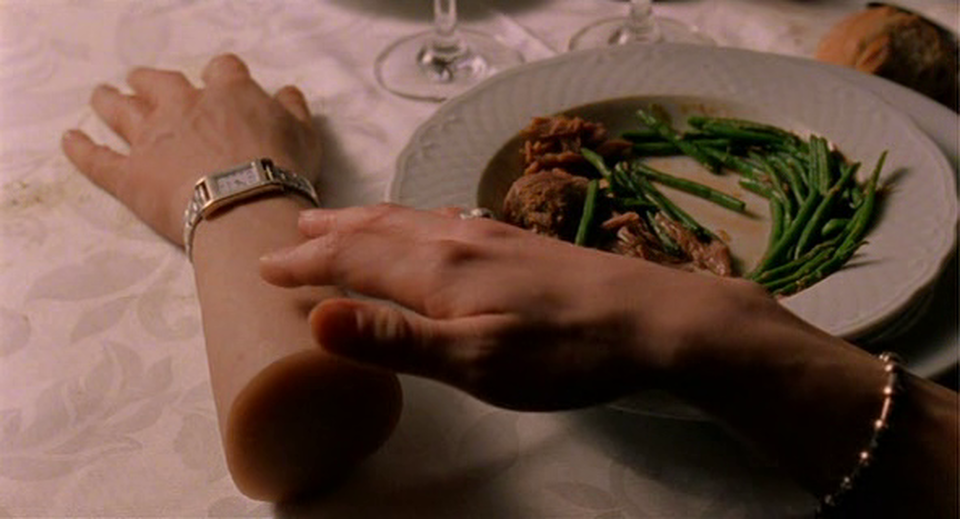

In the most effective and unsettling scene, Esther drinks too much wine which, along with her anxiety, contributes to making her more and more withdrawn from the environment. The numbness manifests itself in her body as the woman hallucinates that her hand literally detaches itself and lies on table disconnected from the rest of her body. The feeling of detachment is embodied by the sound design of the restaurant clutter - laughs, talks, sound of cutlery scratching the plates - intensifies. This scene brings to mind Polanski’s Repulsion (1965), the only other film I can think of that studies the body in such a compelling way, and the close shots of a rotten, skinned rabbit that would accompany the images of Carol’s inner terror. In contrast to Polanski’s heroine, however, the only way for Esther to escape from numbness and detachment is through self-mutilation. The increasing urge to deepen her injury once again is illustrated by the juxtaposition of the vivid close up of food with Esther scratching maniacally her hand.

Subsequently, the act - that sits on the verge of self-cannibalism - that she carries out after the failed business dinner resembles an intimate sexual copulation with herself. It’s the heroine’s way of feeling again, to bring herself back to life. It’s almost as if she has to get into the deepest part of her flesh to come to terms with world and reality around her. Through self-cannibalism and destruction of her body, Esther discovers a special kind of intimate relationship with her own corporeal self and the film shows the poetry and beauty of this unsettling bloody spectacle. As she studies her body, Esther exhibits cannibalistic voyeurism. This is especially emphasised in the final sequence when Esther takes time to observe her body, now transformed with open wounds and tender, naked flesh. The reference to the Deleuzian notion of “flesh” is blatantly clear. Daniela Voss noted that ‘although “meat” and “flesh” are both metaphysical concepts and created under the influence of pictorial art, they are signs of two very different modes of thinking. Deleuze’s metaphysics of becoming calls for resistance toward the intolerable in the present.’ Whereas for Merleau-Ponty, who engaged his work in the investigation of the above concepts, ontology of the flesh presents a comprehensive and conciliatory “Weltanschauung”, a theatre of the visible and the invisible, which puts us at peace with the world and our fellow beings’ (Voss, 2013:1) Both approaches relate to In My Skin with its gripping portrayal of the unstoppable urge to reconnect with the body by detaching from it. To see what we are refused by nature, to see the most deeply hidden secret…the flesh.

Aside from observing her body, Esther wants to be observed. The urge of performing her self-cannibalistic spectacle now demands a witness. Hence, her camera fulfils her desire to both look and be looked at as she’s able to analyse, study and admire the pictures later. They preserve her act of mutilation better than formalin would, although, they don’t bring it back to life. It is dead as her cut skin with the exception of their flattened, one dimensional version in her camera. Similarly, the film preserves not reality but the film’s distorted version of it. Esther’s failed attempt to mummify her own skin, therefore, stands as a powerful allegory for the fragile nature of cinema, inevitably connected to the sense of lack.

Subsequently, the act - that sits on the verge of self-cannibalism - that she carries out after the failed business dinner resembles an intimate sexual copulation with herself. It’s the heroine’s way of feeling again, to bring herself back to life. It’s almost as if she has to get into the deepest part of her flesh to come to terms with world and reality around her. Through self-cannibalism and destruction of her body, Esther discovers a special kind of intimate relationship with her own corporeal self and the film shows the poetry and beauty of this unsettling bloody spectacle. As she studies her body, Esther exhibits cannibalistic voyeurism. This is especially emphasised in the final sequence when Esther takes time to observe her body, now transformed with open wounds and tender, naked flesh. The reference to the Deleuzian notion of “flesh” is blatantly clear. Daniela Voss noted that ‘although “meat” and “flesh” are both metaphysical concepts and created under the influence of pictorial art, they are signs of two very different modes of thinking. Deleuze’s metaphysics of becoming calls for resistance toward the intolerable in the present.’ Whereas for Merleau-Ponty, who engaged his work in the investigation of the above concepts, ontology of the flesh presents a comprehensive and conciliatory “Weltanschauung”, a theatre of the visible and the invisible, which puts us at peace with the world and our fellow beings’ (Voss, 2013:1) Both approaches relate to In My Skin with its gripping portrayal of the unstoppable urge to reconnect with the body by detaching from it. To see what we are refused by nature, to see the most deeply hidden secret…the flesh.

Aside from observing her body, Esther wants to be observed. The urge of performing her self-cannibalistic spectacle now demands a witness. Hence, her camera fulfils her desire to both look and be looked at as she’s able to analyse, study and admire the pictures later. They preserve her act of mutilation better than formalin would, although, they don’t bring it back to life. It is dead as her cut skin with the exception of their flattened, one dimensional version in her camera. Similarly, the film preserves not reality but the film’s distorted version of it. Esther’s failed attempt to mummify her own skin, therefore, stands as a powerful allegory for the fragile nature of cinema, inevitably connected to the sense of lack.

The film’s director, Marina De Van took the desire of total cinematic embodiment to the extreme in the very act of preparation for the shoot as she casted herself as her own protagonist. For a year she was conducting acting exercises in order to convincingly portray Esther’s self detachment, such as buying and wearing uncomfortable shoes or clothes that were too small, walking out of her comfort zone by stylising her hair against her personal preferences, growing her fingernails to uncomfortable lengths. The process, therefore, became a peculiar act of bodily self-examination and analysis. De Van graduated from La Fémis, a prestigious French film school known for its innovative approach to teaching the craft and inspires the students to look for new ways of seeing and speaking to the audience. The school gave the young director a chance to meet François Ozon with whom she created a fruitful relationship collaborating on many productions including 8 Women. Ozon described De Van as his female counterpart and the influence of the prolific provocateur is certainly present in In My Skin, where she fully sacrifices herself for the film.

As I examined briefly the cinematic body of In My Skin, I am going to move into the national. Although the filmmaker herself refuses broader interpretations, it is useful to look through its references to French history and current socio-political landscape of France. Firstly, it is important to consider the events that took place during World War II. The Nazi German defeat of France is still a sensitive topic, evoking a deeply seeded national guilt. If we look at Esther and her body as a personification of France, the maniacal, obsessive need to dig further into the wound may be seen as a manifestation of this unspoken, demonic shame. In My Skin can be regarded as a statement of urgency for national catharsis that can be only fully experienced through the body because the psyche refuses to face it.

Similarly, when Esther injures herself for the first time, she is shocked and disgusted at the beginning but that is quickly replaced with voyeuristic curiosity. What is striking though, is that she escapes from the uneasiness caused by her numbness to pain, by calmly going out for a can of coke. A motif that comes back during the final scene. While mutilating her own body, Esther quenches her thirst with a coke and other American soft drinks. It opens the possibility to find references to Americanisation of France as the country escapes from its unresolved issues. The problems of American values such as capitalism and consumerism, and the issue of foreign influence on France are brought up again at the dinner that Esther has with her clients. They discuss the superiority of France over Japan and Italy. Similarly, Esther’s special professional interest in the Middle East echoes the inner tension that France experiences with immigration from this region. In this multicultural context it is useful to also bring up the differences in understanding body language across the countries and nations that have been mentioned by Esther’s clients during the dinner. The promotional images, that were perfectly acceptable in Western culture, have been declined by a Japanese company as they apparently would connote offensive messages.

Lastly, there is the universal body of everyday man with anxieties that seem to be even more relatable almost two decades later with the advent of digital media. The problems that Esther experiences are caused by the pressure she puts on herself at work and in her relationship. The detachment and alienation that have haunted Western civilisation and became more intense in the era of omnipresent smartphones and constant streams of information. As Oliver du Bruyn remarks:

‘The beauty of Dans ma peau also lies in the way its tale of violence of social relations in the modern working environment is embedded in the film [and it belongs ] to the filiation of those unclassifiedable directors (from Georges Franju to Roman Polansky), for who deviancy is first and foremost poetic and aesthetic experience. The mutilation, the fragmentation that is the topic of the film affects the form of the film itself’ (Beugnet, 2007: 158).

De Van’s film suggests that the cure may lie in separating body from soul, an approach that civilisation keeps refusing.

The bodies I uncovered that are hidden in Marina de Van’s unsettling and gripping film let me only begin to grasp the essence of In My Skin. I consider it one of the most important films of French Extremism, one that explores and embodies the main characteristics of the movement.

Next Friday, I am going to continue the adventure in the New French Extremist universe, this time travel to the darkest cinematic corners to deeply examine Martyrs, France’s most distressing and agitating films to date!

by Paulina

As I examined briefly the cinematic body of In My Skin, I am going to move into the national. Although the filmmaker herself refuses broader interpretations, it is useful to look through its references to French history and current socio-political landscape of France. Firstly, it is important to consider the events that took place during World War II. The Nazi German defeat of France is still a sensitive topic, evoking a deeply seeded national guilt. If we look at Esther and her body as a personification of France, the maniacal, obsessive need to dig further into the wound may be seen as a manifestation of this unspoken, demonic shame. In My Skin can be regarded as a statement of urgency for national catharsis that can be only fully experienced through the body because the psyche refuses to face it.

Similarly, when Esther injures herself for the first time, she is shocked and disgusted at the beginning but that is quickly replaced with voyeuristic curiosity. What is striking though, is that she escapes from the uneasiness caused by her numbness to pain, by calmly going out for a can of coke. A motif that comes back during the final scene. While mutilating her own body, Esther quenches her thirst with a coke and other American soft drinks. It opens the possibility to find references to Americanisation of France as the country escapes from its unresolved issues. The problems of American values such as capitalism and consumerism, and the issue of foreign influence on France are brought up again at the dinner that Esther has with her clients. They discuss the superiority of France over Japan and Italy. Similarly, Esther’s special professional interest in the Middle East echoes the inner tension that France experiences with immigration from this region. In this multicultural context it is useful to also bring up the differences in understanding body language across the countries and nations that have been mentioned by Esther’s clients during the dinner. The promotional images, that were perfectly acceptable in Western culture, have been declined by a Japanese company as they apparently would connote offensive messages.

Lastly, there is the universal body of everyday man with anxieties that seem to be even more relatable almost two decades later with the advent of digital media. The problems that Esther experiences are caused by the pressure she puts on herself at work and in her relationship. The detachment and alienation that have haunted Western civilisation and became more intense in the era of omnipresent smartphones and constant streams of information. As Oliver du Bruyn remarks:

‘The beauty of Dans ma peau also lies in the way its tale of violence of social relations in the modern working environment is embedded in the film [and it belongs ] to the filiation of those unclassifiedable directors (from Georges Franju to Roman Polansky), for who deviancy is first and foremost poetic and aesthetic experience. The mutilation, the fragmentation that is the topic of the film affects the form of the film itself’ (Beugnet, 2007: 158).

De Van’s film suggests that the cure may lie in separating body from soul, an approach that civilisation keeps refusing.

The bodies I uncovered that are hidden in Marina de Van’s unsettling and gripping film let me only begin to grasp the essence of In My Skin. I consider it one of the most important films of French Extremism, one that explores and embodies the main characteristics of the movement.

Next Friday, I am going to continue the adventure in the New French Extremist universe, this time travel to the darkest cinematic corners to deeply examine Martyrs, France’s most distressing and agitating films to date!

by Paulina

Bibliography

Barker, J., The Tactile Eye, 2009: University of California Press

Beugnet, M., Cinema and sensation [electronic resource] : French film and the art of transgression, 2007: Edinburgh University Press

Palmer, T., Under your skin: Marina de Van and the contemporary French cinéma du corps, 2007: [https://doi.org/10.1386/sfci.6.3.171_1]

Voss, D. Philosophical Concept of Meat and Flesh: Deleuze and Merleau-Ponty, 2013: PARRHESIA

Beugnet, M., Cinema and sensation [electronic resource] : French film and the art of transgression, 2007: Edinburgh University Press

Palmer, T., Under your skin: Marina de Van and the contemporary French cinéma du corps, 2007: [https://doi.org/10.1386/sfci.6.3.171_1]

Voss, D. Philosophical Concept of Meat and Flesh: Deleuze and Merleau-Ponty, 2013: PARRHESIA