Queer Temporality and Digital Touch in Taiwanese Digital Films 17/12/2021

We inhabit the era of the anthropocene, in which human activity became the dominant geological force, effectuating dramatic atmospheric transformations and affecting all Earthly life. Nature, from which humans detatched themselves, blinded by the idea of continuous progress which depends on the extraction of natural resources, returns with vengeance, dethroning the figure of the Anthropos as master and owner of the universe. Climatic anomalies such as tsunamis, floods and fires, in combination with the current COVID-19 pandemic require us to embrace change and unpredictability as the only constant, vital force. Alas, human perception, clinging to unified identity and subjectivity, is not capable of adjusting to this new reality and actively partaking in its creation. A universe where becoming is the only form of existence is ultimately a queer world, where fluidity and malleability is inherent to matter.

This article investigates the way in which queerness is embodied and constructed in three short Taiwanese films: Echo Each Other/呼叫冥王星 ( Pin-ru Chen, Taiwan, 2016) Body at Large/晃遊身體 (Ying Cheng-ju, Taiwan, 2012) and Adorable (Cheng-Hsu Chung, Taiwan/UK, 2018) in particular, we focus on the way these films explore the potential of digital technologies to affectively queer temporality and space, touching our bodies and becoming a part of our nervous systems allowing for a simultaneous queering of our perception. Following Henri Bergson¹, we demonstrate that temporality is not homogenous, but rather composed of a multiplicity of singular durations. By conducting close textual analysis, we investigate how these Taiwanese productions queer time and space, foregrounding aesthetics that shatter the scopic regime, associated with the dominant heterosexual framework, and instead catalyse a tactile, sensory viewing experience. The study embraces a film-philosophical framework grounded in the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari², as well as queer theory that moves beyond its institutional Anglo-American form. Thus, in this article we will rely on theories that do not cancel the body but rather affirm it.³ In this context, we consider the act of spectatorship as inseparable from the film itself, paying close attention to the multifarious bodies that partake in the filmic assemblage: that of the viewer, of the film itself, as well as the bodies we can discern onscreen.

These films and their digital bodies traverse national borders and, in a time when actual touch is restricted by the pandemic, they offer us instead a desirous virtual touch, as they touch us with their tactile aesthetics, begetting what Laura Marks termed ‘haptic visuality‘⁴. Being available for global audiences through the streaming websites Vimeo and Gagaoolala, these works exist as a part of worldwide-integrated screen culture, what Patricia Pisters, following Deleuze’s film-philosophical works, described as a digital ‘neuro-image’⁵. Its anchoring in the dimension of the future allows for the creation of novelty that exceeds the boundaries imposed by the priapic, heteronormative reign of late capitalism. The films can be seen as producing the world and people of the future, woven by the force of queer desire which embodied on screen catalyse in us affects and intensities that beget the alien, queer desire for the image itself.

This article investigates the way in which queerness is embodied and constructed in three short Taiwanese films: Echo Each Other/呼叫冥王星 ( Pin-ru Chen, Taiwan, 2016) Body at Large/晃遊身體 (Ying Cheng-ju, Taiwan, 2012) and Adorable (Cheng-Hsu Chung, Taiwan/UK, 2018) in particular, we focus on the way these films explore the potential of digital technologies to affectively queer temporality and space, touching our bodies and becoming a part of our nervous systems allowing for a simultaneous queering of our perception. Following Henri Bergson¹, we demonstrate that temporality is not homogenous, but rather composed of a multiplicity of singular durations. By conducting close textual analysis, we investigate how these Taiwanese productions queer time and space, foregrounding aesthetics that shatter the scopic regime, associated with the dominant heterosexual framework, and instead catalyse a tactile, sensory viewing experience. The study embraces a film-philosophical framework grounded in the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari², as well as queer theory that moves beyond its institutional Anglo-American form. Thus, in this article we will rely on theories that do not cancel the body but rather affirm it.³ In this context, we consider the act of spectatorship as inseparable from the film itself, paying close attention to the multifarious bodies that partake in the filmic assemblage: that of the viewer, of the film itself, as well as the bodies we can discern onscreen.

These films and their digital bodies traverse national borders and, in a time when actual touch is restricted by the pandemic, they offer us instead a desirous virtual touch, as they touch us with their tactile aesthetics, begetting what Laura Marks termed ‘haptic visuality‘⁴. Being available for global audiences through the streaming websites Vimeo and Gagaoolala, these works exist as a part of worldwide-integrated screen culture, what Patricia Pisters, following Deleuze’s film-philosophical works, described as a digital ‘neuro-image’⁵. Its anchoring in the dimension of the future allows for the creation of novelty that exceeds the boundaries imposed by the priapic, heteronormative reign of late capitalism. The films can be seen as producing the world and people of the future, woven by the force of queer desire which embodied on screen catalyse in us affects and intensities that beget the alien, queer desire for the image itself.

Sexual Temporality of The Future: Neuro-Image and Cinesexuality

Before we dive into analysis of the films it is important to provide a brief overview of the theoretical framework that guides our immersive approach to these works.

Drawing on Deleuze and Guattari’s transcendental empiricism, we regard desire not in terms of psychoanalytic lack and eternal unfulfillment, but rather as productive, striving for creation of novel connections.

We theorise the viewer not as a subject with stable identity and unitary subjectivity, but rather as an embodied amalgamation of speeds and slownesses, interacting with each other. Allowing our bodies to be affected by the filmic image – also conceived as a relation of forces – we enter into machinic assemblage with it, shedding unitary subjectivity and entering into the process of becoming-other. This is a novel, generative way of being that embraces relations and connections over resemblance, identity and analogy. Patricia MacCormack termed this affective mode of viewership as cinesexuality: ’what cinema is cannot be known, its affectivity and our ecstasies are limited only to the extent we limit desire, and, as all cinesexuals know, cinema brings to us the unbearable excess of the simplest planes within an image’⁶. Through affective abundance, cinesexual encounters transform our bodies into a depersonalized, intensive Body without Organs which ‘is opposed less to organs as such than to the organization of the organs insofar as it composes an organism. The body without organs is not a dead body but a living body all the more alive and teeming once it has blown apart the organism and its organization’⁷. Films experienced cinesexually are capable of creating fertile ground where new solutions can be found with creativity and openness towards new understandings of the human.

This cinesexual spectatorship shatters linear temporality – the Stoic time Chronos – and instead begets the generative Kairos: ‘time ready to be seized, an expression of timeliness, a critical juncture where something could happen’⁸. Pisters relates this time of ephemeral opportunity to her Deleuze-inspired concept of neuro-image. In his Cinema books, Deleuze distinguishes between movement- and time-images associated with the sensory-motor schemata of classical cinema and the crystalline structure of modern cinema that appeared after WWII, where the logical connection between images becomes broken and time is unleashed from its linear constraints⁹. Pisters¹⁰ discerned neuro-image as another type of time-image which is connected to 9/11 and widespread digital technologies as a caesura which destabilised the Western conceptualisation of subjectivity. This displacement is expressed by filmmakers rejecting narrative structure and instead opting for the logic of the database that stands for the ‘nonlinear collection of items’¹¹.

This database logic can be connected to the temporality of neuro-image, which Pisters grounds in the dimension of the future, drawing on Deleuze’s philosophy of time and the three temporal syntheses of past, present and future. The neuro-image is grounded in the third synthesis where the future serves as a base for the past and present; the three-in-one: Past, Present, Future are co-present in the film, revealing time itself as heterogenous and allowing for creation of the new worlds. The films below can be considered neuro-images, located in the interface between database and narrative, ‘producing a shock to thought, communicating vibrations to the cortex, touching the nervous and cerebral system directly’¹². They touch our bodies and minds, catalysing in us transformative queer desire, revealing representation as matter which is incessantly vibrant.

Drawing on Deleuze and Guattari’s transcendental empiricism, we regard desire not in terms of psychoanalytic lack and eternal unfulfillment, but rather as productive, striving for creation of novel connections.

We theorise the viewer not as a subject with stable identity and unitary subjectivity, but rather as an embodied amalgamation of speeds and slownesses, interacting with each other. Allowing our bodies to be affected by the filmic image – also conceived as a relation of forces – we enter into machinic assemblage with it, shedding unitary subjectivity and entering into the process of becoming-other. This is a novel, generative way of being that embraces relations and connections over resemblance, identity and analogy. Patricia MacCormack termed this affective mode of viewership as cinesexuality: ’what cinema is cannot be known, its affectivity and our ecstasies are limited only to the extent we limit desire, and, as all cinesexuals know, cinema brings to us the unbearable excess of the simplest planes within an image’⁶. Through affective abundance, cinesexual encounters transform our bodies into a depersonalized, intensive Body without Organs which ‘is opposed less to organs as such than to the organization of the organs insofar as it composes an organism. The body without organs is not a dead body but a living body all the more alive and teeming once it has blown apart the organism and its organization’⁷. Films experienced cinesexually are capable of creating fertile ground where new solutions can be found with creativity and openness towards new understandings of the human.

This cinesexual spectatorship shatters linear temporality – the Stoic time Chronos – and instead begets the generative Kairos: ‘time ready to be seized, an expression of timeliness, a critical juncture where something could happen’⁸. Pisters relates this time of ephemeral opportunity to her Deleuze-inspired concept of neuro-image. In his Cinema books, Deleuze distinguishes between movement- and time-images associated with the sensory-motor schemata of classical cinema and the crystalline structure of modern cinema that appeared after WWII, where the logical connection between images becomes broken and time is unleashed from its linear constraints⁹. Pisters¹⁰ discerned neuro-image as another type of time-image which is connected to 9/11 and widespread digital technologies as a caesura which destabilised the Western conceptualisation of subjectivity. This displacement is expressed by filmmakers rejecting narrative structure and instead opting for the logic of the database that stands for the ‘nonlinear collection of items’¹¹.

This database logic can be connected to the temporality of neuro-image, which Pisters grounds in the dimension of the future, drawing on Deleuze’s philosophy of time and the three temporal syntheses of past, present and future. The neuro-image is grounded in the third synthesis where the future serves as a base for the past and present; the three-in-one: Past, Present, Future are co-present in the film, revealing time itself as heterogenous and allowing for creation of the new worlds. The films below can be considered neuro-images, located in the interface between database and narrative, ‘producing a shock to thought, communicating vibrations to the cortex, touching the nervous and cerebral system directly’¹². They touch our bodies and minds, catalysing in us transformative queer desire, revealing representation as matter which is incessantly vibrant.

Echo Each Other: The Liquid Language of Difference

Echo Each Other blends urban drama with surreal fairy-tale as it poetically explores the potential of embodied communication through the story of two deaf young women, living together in a small urban jungle apartment. They are subsequently revealed as a pair of mermaid princesses (Zhao Wanting and Nian Pixuan), who exchange their voices for human legs, therefore indicating their inherent difference; queerness that cuts through their human identity. This supernatural aspect collapses the temporal dimension of the film, introducing a conflicting, otherworldly and alien temporality. The temporal architecture of the film is additionally complicated by the fragmented narrative structure, installing us in in the temporality of Kairos that begets the creation of Difference in itself.

The protagonists, as mermaids, can be seen as an embodiment of present-day sirens – digital devices and communication technologies: the telephone, radio waves which evoke the digital interconnectivity of late capitalism. Moreover, Echo Each Other almost entirely eschews spoken dialogue to concentrate on the affective embodiment of sign language, additionally highlighted by the expressive aesthetics, such as use of slow shutter speed and handheld camera movements, image inversion and computer-generated graphics. In combination with neon colours and flickering effects, the film transports us into a tactile universe of sensory abundance, it touches us with its digital body, inviting us into a desirous encounter.

In this context, both the sign language as a mode of communication between characters, and the sensory language of the film, can be considered as ‘the minor gesture [which] does not have the full force of preexisting status, of a given structure…It is out of time, untimely, rhythmically inventing its own pulse’¹³. Such gesture prompts us to abandon the sensory-motor schemata of movement-image with its insistence on cognitive coherence and instead incites us to open our bodies to the forces of machinic desire catalysed by our intensive, cinesexual alliance with the image. Through this minor gesture hypnotising us with inhuman speed unleashed by the potential of digital technology. This is evident in the opening sequence where one of the protagonists travels by taxi through the urban landscape: the fast editing and motion blur evoke the inhuman speed of city life. The logic of Chronos is additionally disturbed by the otherworldly soundscape composed of “metallic”, abstract sounds mixed with amplified sounds of human breath. The frantic montage is followed by a long shot of a woman standing with her suitcase at night on a bridge that cuts to the close up of the suitcase drifting in the water. The emphasis on in-between spaces and transitory states – taxi, marketplace, water – indicate the film’s attempt to evoke the liquidity of matter and subjectivity. Similarly, the digital body with its database plasticity and malleability can be seen as ultimately queer, allowing for the creation of new worlds and peoples.

The film communicates with us though the ubiquity of water in its various states – steam coming out of a kettle, water in the aquarium, close ups of the sea. Clocks are also omnipresent, but instead of measuring time, they rather emphasise its fractions and disintegration – linear Chronos becomes entropic Kairos, where chance and opportunity reign allowing for the creation of novel modes of thought. This, however, is not a mode of communication supported by global capitalism that hails the symbolic over embodied language. Here it is helpful to invoke Irigaray’s¹⁴ philosophy of sexual difference that Western culture attempts to discursively conceal and instead impose priapic sameness on the singularity of the feminine. As Lucy Bolton notes, Irigaray’s philosophy of sexual difference contains immanent cinematic qualities in her poetic, visual evocation of female morphology. As Bolton asserted, ‘Irigaray suggests non-linguistic modes of contact that might move outside of the symbolic and questions of female language, without consigning women to the real or excluding them altogether’¹⁵.

This non-linguistic communication is emphasized in the film also through the embodied camera movement that frantically probes the space with its inhuman camera-eye, following the characters or lingering on the objects in the apartment. This is cinema of the body, where the ‘daily attitude puts the before and the after into the body, time into the body, the body as a revealer of the deadline’¹⁶ This temporal physicality is additionally heightened by electronic sounds recalling the internal music of human bodies, combined with rhythmical breathing. The tactile aesthetics of Echo Each Other allow this singular femininity to become unchained from the territorialising constraints of priapic capitalism. This is femininity yet to come, that has not yet had a chance to be fully actualised, repressed by the priapic regime of sexuality; femininity without identity but captured in a transitory, queer space of becoming.

The protagonists, as mermaids, can be seen as an embodiment of present-day sirens – digital devices and communication technologies: the telephone, radio waves which evoke the digital interconnectivity of late capitalism. Moreover, Echo Each Other almost entirely eschews spoken dialogue to concentrate on the affective embodiment of sign language, additionally highlighted by the expressive aesthetics, such as use of slow shutter speed and handheld camera movements, image inversion and computer-generated graphics. In combination with neon colours and flickering effects, the film transports us into a tactile universe of sensory abundance, it touches us with its digital body, inviting us into a desirous encounter.

In this context, both the sign language as a mode of communication between characters, and the sensory language of the film, can be considered as ‘the minor gesture [which] does not have the full force of preexisting status, of a given structure…It is out of time, untimely, rhythmically inventing its own pulse’¹³. Such gesture prompts us to abandon the sensory-motor schemata of movement-image with its insistence on cognitive coherence and instead incites us to open our bodies to the forces of machinic desire catalysed by our intensive, cinesexual alliance with the image. Through this minor gesture hypnotising us with inhuman speed unleashed by the potential of digital technology. This is evident in the opening sequence where one of the protagonists travels by taxi through the urban landscape: the fast editing and motion blur evoke the inhuman speed of city life. The logic of Chronos is additionally disturbed by the otherworldly soundscape composed of “metallic”, abstract sounds mixed with amplified sounds of human breath. The frantic montage is followed by a long shot of a woman standing with her suitcase at night on a bridge that cuts to the close up of the suitcase drifting in the water. The emphasis on in-between spaces and transitory states – taxi, marketplace, water – indicate the film’s attempt to evoke the liquidity of matter and subjectivity. Similarly, the digital body with its database plasticity and malleability can be seen as ultimately queer, allowing for the creation of new worlds and peoples.

The film communicates with us though the ubiquity of water in its various states – steam coming out of a kettle, water in the aquarium, close ups of the sea. Clocks are also omnipresent, but instead of measuring time, they rather emphasise its fractions and disintegration – linear Chronos becomes entropic Kairos, where chance and opportunity reign allowing for the creation of novel modes of thought. This, however, is not a mode of communication supported by global capitalism that hails the symbolic over embodied language. Here it is helpful to invoke Irigaray’s¹⁴ philosophy of sexual difference that Western culture attempts to discursively conceal and instead impose priapic sameness on the singularity of the feminine. As Lucy Bolton notes, Irigaray’s philosophy of sexual difference contains immanent cinematic qualities in her poetic, visual evocation of female morphology. As Bolton asserted, ‘Irigaray suggests non-linguistic modes of contact that might move outside of the symbolic and questions of female language, without consigning women to the real or excluding them altogether’¹⁵.

This non-linguistic communication is emphasized in the film also through the embodied camera movement that frantically probes the space with its inhuman camera-eye, following the characters or lingering on the objects in the apartment. This is cinema of the body, where the ‘daily attitude puts the before and the after into the body, time into the body, the body as a revealer of the deadline’¹⁶ This temporal physicality is additionally heightened by electronic sounds recalling the internal music of human bodies, combined with rhythmical breathing. The tactile aesthetics of Echo Each Other allow this singular femininity to become unchained from the territorialising constraints of priapic capitalism. This is femininity yet to come, that has not yet had a chance to be fully actualised, repressed by the priapic regime of sexuality; femininity without identity but captured in a transitory, queer space of becoming.

Body At Large: Powers of False and the Ceremonial Bodies

This experimental documentary investigates the problems faced by borderline gender people in Taiwan – a nation still haunted by the memory of sexual prohibition that lingers in the collective Taiwanese consciousness. Despite the current more progressive gender politics in Taiwan, the memories of vigorous repressions of nonheteronormative modes of sexuality by the Taiwanese nationalist government (KMT), which included unscrupulous surveillance of sexual life in Taiwan. The repressive model of gendered sexual subjectivity was constructed by KMT during the Cold War and radicalised during the AIDS pandemic. By aligning the Confucian ethics of the virtue of state, anti-prostitution feminists helped to install ‘social order premised on “sage-king” police/civil servant/student-nationalist citizen subject position’ and saw prostitution as inherently linked to homosexuality¹⁷.

Body at Large evokes these painful national memories, albeit indirectly, by portraying the stories of four queer subjects: visual artist and critic Alphonse Perroquet Quail Youth-Leigh, the bodybuilder Lee Yao, make-up artist AG, and transgender actor James Chen. They are depicted as unable to conform to any stable identity, they seem to be residing in the transitory space of perpetual becoming. They are caught in the eternal in-between, but only there their bodies can be unchained from the prison of heteronormative signification. Youth-Leigh is especially direct when he states that he cannot describe himself entirely as a homosexual but rather that he is possessed by homosexual obsession grounded in visual attraction to the appearance of young boys. Though he calls it visual obsession, this visuality is tactile and haptic and enables him to touch male bodies with his camera-eye, while he makes films. This haptic visuality is also engendered by our encounter with the documentary when we are exposed to queer, and often nude, bodies of the participants.

The film queers the genre of documentary through aesthetic blending the fiction and reality: the dimension of profilmic and putative realities blend through the ubiquity of screens and cameras that reveal multiple films-in-the-film, shattering linear narrative and embracing the potential of algorithmic manipulation of the malleable database. This creative transformation of reality is what Deleuze, following Nietzsche, described as ‘the powers of false’, when narration and description become falsifying and cease to be truthful¹⁸. As Deleuze explained, powers of false unleash ‘the power of becoming which constitutes series or degrees, which crosses limits, carries out metamorphoses, and develops along its whole path an act of legend, of story-telling. Beyond the true or the false, becoming as power of the false’¹⁹. The effects of this are evident in the opening scene which consists of a sensory montage introducing us to the figure of Youth-Leigh. He is portrayed through blurred focus, inverted image and superimpositions that endow the rhythm of the film with a liquid quality and splits homogenous temporality into a multiplicity of singular durations. The soundscape is composed of overlapping voices that express their contrasting opinions of Youth-Leigh, creating creative disjunction between aural visual dimensions, additionally splitting the figure of protagonists. It thus affectively exposes the process of construction of “truth" in the age of digital manipulability.

The dislocations and fragmentations are also expressed through the film’s portrayal of the bodies of the documentary’s subjects, AG, and the transgender James Chen seem more comfortable with their queer bodies, with Chen successfully performing male and female roles, while Youth-Leigh and Lee Yao embody the struggle of not being able to fit into stable categories. Lee and his drag alter ego, Phantom Queen, is caught between the pressure to conform to the heteronormative model of masculinity (that he tries to reach by practicing body-building), and the desire to break free from this subjugating regime of sexuality. This is embodied through the film’s aesthetic differentiation between Yao in the gym, shot using realist techniques such as handheld camera and natural lighting, and highly dramatic and sensual scenes depicting Phantom Queen, with the camera slowly caressing her body, moving along it in close-up with classical music playing, constructing a sense of Apollonian sublime. She is illuminated by the images played on the screens she is surrounded by, splitting time into heterogenous durations. This contrast between Yao Lee, the body builder, and Phantom Queen, the crossdresser, recalls Deleuze’s notion of ceremonial body. As he remarked, ‘it is no longer a matter of following the everyday body, but of making it pass through a ceremony… of imposing a carnival or mascaraed on it which makes it into grotesque body, but also brings out of it a gracious and glorious body, until the disappearance of visible body is achieved’²⁰. This is when the queer subjectivity and temporality of neuro-image, Kairos, becomes manifested – the moment when the body is captured between stable boundaries and exists in the middle and through indetermination.

The film ends in this ‘zone of indiscernibility’²¹, neuro-image’s space of becoming, with a long, choreographed sequence depicting the documentary’s subjects appearing in surreal scenery near the sea, communicating with each other through gestures, bodily postures and nudity. Bathed in soft light their bodies glow with transformative openness that is possible only through the vulnerability of nudity in front of the inhuman camera-eye. In the act of cinesexual spectatorship we are also capable of exposing our nude body for the film, that in return offers us its own nudity in the form of affects and intensities.

Body at Large evokes these painful national memories, albeit indirectly, by portraying the stories of four queer subjects: visual artist and critic Alphonse Perroquet Quail Youth-Leigh, the bodybuilder Lee Yao, make-up artist AG, and transgender actor James Chen. They are depicted as unable to conform to any stable identity, they seem to be residing in the transitory space of perpetual becoming. They are caught in the eternal in-between, but only there their bodies can be unchained from the prison of heteronormative signification. Youth-Leigh is especially direct when he states that he cannot describe himself entirely as a homosexual but rather that he is possessed by homosexual obsession grounded in visual attraction to the appearance of young boys. Though he calls it visual obsession, this visuality is tactile and haptic and enables him to touch male bodies with his camera-eye, while he makes films. This haptic visuality is also engendered by our encounter with the documentary when we are exposed to queer, and often nude, bodies of the participants.

The film queers the genre of documentary through aesthetic blending the fiction and reality: the dimension of profilmic and putative realities blend through the ubiquity of screens and cameras that reveal multiple films-in-the-film, shattering linear narrative and embracing the potential of algorithmic manipulation of the malleable database. This creative transformation of reality is what Deleuze, following Nietzsche, described as ‘the powers of false’, when narration and description become falsifying and cease to be truthful¹⁸. As Deleuze explained, powers of false unleash ‘the power of becoming which constitutes series or degrees, which crosses limits, carries out metamorphoses, and develops along its whole path an act of legend, of story-telling. Beyond the true or the false, becoming as power of the false’¹⁹. The effects of this are evident in the opening scene which consists of a sensory montage introducing us to the figure of Youth-Leigh. He is portrayed through blurred focus, inverted image and superimpositions that endow the rhythm of the film with a liquid quality and splits homogenous temporality into a multiplicity of singular durations. The soundscape is composed of overlapping voices that express their contrasting opinions of Youth-Leigh, creating creative disjunction between aural visual dimensions, additionally splitting the figure of protagonists. It thus affectively exposes the process of construction of “truth" in the age of digital manipulability.

The dislocations and fragmentations are also expressed through the film’s portrayal of the bodies of the documentary’s subjects, AG, and the transgender James Chen seem more comfortable with their queer bodies, with Chen successfully performing male and female roles, while Youth-Leigh and Lee Yao embody the struggle of not being able to fit into stable categories. Lee and his drag alter ego, Phantom Queen, is caught between the pressure to conform to the heteronormative model of masculinity (that he tries to reach by practicing body-building), and the desire to break free from this subjugating regime of sexuality. This is embodied through the film’s aesthetic differentiation between Yao in the gym, shot using realist techniques such as handheld camera and natural lighting, and highly dramatic and sensual scenes depicting Phantom Queen, with the camera slowly caressing her body, moving along it in close-up with classical music playing, constructing a sense of Apollonian sublime. She is illuminated by the images played on the screens she is surrounded by, splitting time into heterogenous durations. This contrast between Yao Lee, the body builder, and Phantom Queen, the crossdresser, recalls Deleuze’s notion of ceremonial body. As he remarked, ‘it is no longer a matter of following the everyday body, but of making it pass through a ceremony… of imposing a carnival or mascaraed on it which makes it into grotesque body, but also brings out of it a gracious and glorious body, until the disappearance of visible body is achieved’²⁰. This is when the queer subjectivity and temporality of neuro-image, Kairos, becomes manifested – the moment when the body is captured between stable boundaries and exists in the middle and through indetermination.

The film ends in this ‘zone of indiscernibility’²¹, neuro-image’s space of becoming, with a long, choreographed sequence depicting the documentary’s subjects appearing in surreal scenery near the sea, communicating with each other through gestures, bodily postures and nudity. Bathed in soft light their bodies glow with transformative openness that is possible only through the vulnerability of nudity in front of the inhuman camera-eye. In the act of cinesexual spectatorship we are also capable of exposing our nude body for the film, that in return offers us its own nudity in the form of affects and intensities.

Adorable: Bodies Painted in Time

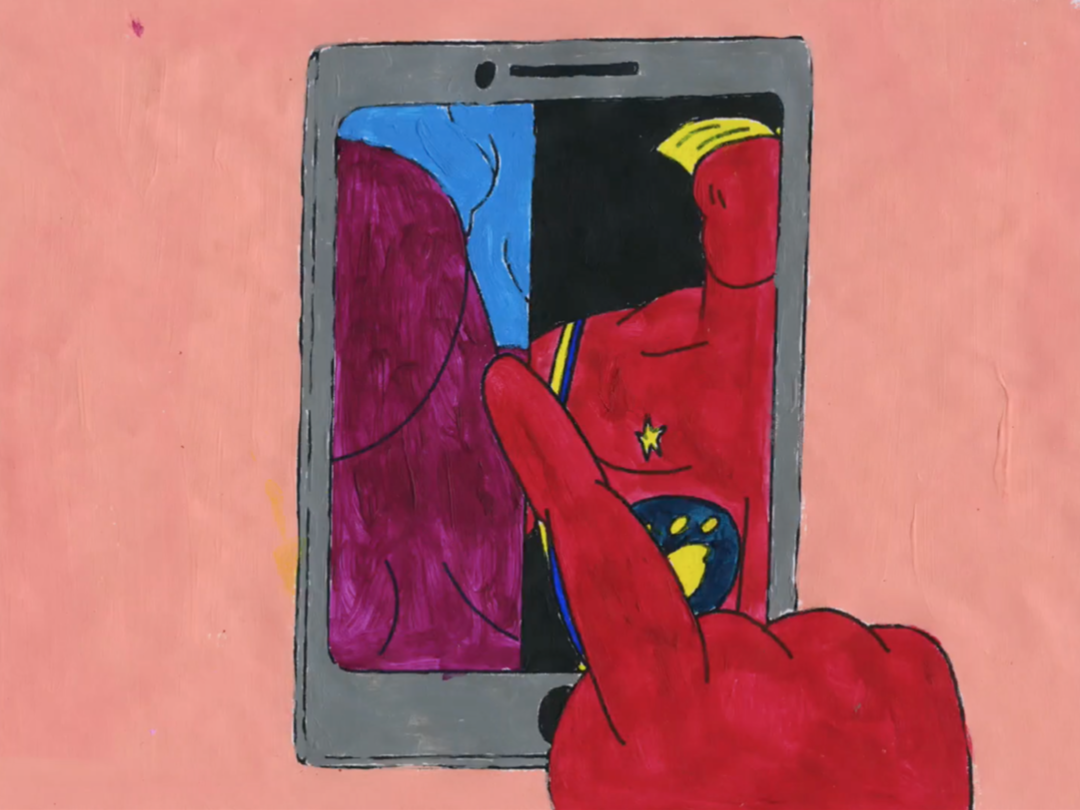

Adorable evokes the exploration of queer sexuality and Taiwanese queer community, which is marked by encounters with exclusion, addictions, queer porn, but also the joy that flows from freeing the body from the matrix of heteronormative signification. Cheng-Hsu Chung’s film, being a hand-painted animation, can be seen as the ultimate affirmation of the powers of false in relation to the digital body. As Jennifer Barker remarked, ‘if cinema is the illusion of continuous motion, animation is the illusion of illusion, and as such it provides a unique opportunity to study this passionate liason between the body and the cinema’²². Animation foregrounds the ultimate liquidity of matter, its vibrancy and ability to morph and change – its drive to untameable becoming. Hence, we can assert that animation is an inherently queer art, which affectively investigates bodily and perceptual limits. The production process – the hand-panting of each frame – can be regarded as a literal evocation of Lev Manovich’s suggestion that digital media can paint in time, creating a discernibly imperfect texture of the image translated into digital film-body²³.

The filmic universe into which Adorable transports us is located in non-Euclidean space, where none of the Earthy physical laws are valid. The bodies that appear onscreen become continuously disintegrated and morphed into new assemblages, while symbolic shapes, such as the phallic signifier transform into absolute abstraction. Sound design created by Joe Farley vastly contributes to the tactility of the images, with sound effects providing us with hints to interpret the narrative. In order to enter this queer world of perceptual paradoxes we need cinesexual openness that allows for the corporeal, intuitive attention to a-signifying, de-territorializing, affectual qualities of the film. Through immersing ourselves in the rhythm of metamorphosis that materialises onscreen, we eschew the desire for coherency and signification. This leads us into the threshold of perception, endowing us with a unique, non-drug induced psychedelic experience that allows us to see a reality inaccessible to humans.

Through its depiction of screens, the animation evokes the online, virtual reality where many queer people start their adventure of sexual self-discovery through porn, social media, chats, and forums. The screens merge into one another and into other shapes and figures, luring us into a cinesexual assemblage in which our subjectivity dissolves and our body becomes a body-without-organs – intensive and affectively disorganised. Actual and virtual, object and observer, matter and mental construction all become indiscernible and we are being granted an entrance into the queer kingdom of fluidity, malleability and becoming.

The filmic universe into which Adorable transports us is located in non-Euclidean space, where none of the Earthy physical laws are valid. The bodies that appear onscreen become continuously disintegrated and morphed into new assemblages, while symbolic shapes, such as the phallic signifier transform into absolute abstraction. Sound design created by Joe Farley vastly contributes to the tactility of the images, with sound effects providing us with hints to interpret the narrative. In order to enter this queer world of perceptual paradoxes we need cinesexual openness that allows for the corporeal, intuitive attention to a-signifying, de-territorializing, affectual qualities of the film. Through immersing ourselves in the rhythm of metamorphosis that materialises onscreen, we eschew the desire for coherency and signification. This leads us into the threshold of perception, endowing us with a unique, non-drug induced psychedelic experience that allows us to see a reality inaccessible to humans.

Through its depiction of screens, the animation evokes the online, virtual reality where many queer people start their adventure of sexual self-discovery through porn, social media, chats, and forums. The screens merge into one another and into other shapes and figures, luring us into a cinesexual assemblage in which our subjectivity dissolves and our body becomes a body-without-organs – intensive and affectively disorganised. Actual and virtual, object and observer, matter and mental construction all become indiscernible and we are being granted an entrance into the queer kingdom of fluidity, malleability and becoming.

Virtual World of Queer Becoming

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a further move of cinema on-line, providing novel techniques of film circulation and encouraging the transnational flow of creative content. Space and time become transformed and the borders traversed, allowing for intercultural, non-fetishist exchange. As a European student in British university, the encounters with these films allow me to touch the Taiwanese culture not as Other but as Difference. Thus, this study is a manifestation of my deep desire to engage with these works without imposing a Eurocentric framework, and I find the cinesexual mode of spectatorship as the most ethical encounter with Difference.

The films evoked above, through affective techniques such as the use of slow shutter speed, unexpected juxtaposition of aural and visual elements, or the “schizophrenic” cinematography where the camera swirls, drawn into unpredictable angles, allow us to shed our unified identity. These audio-visual works require viewers to eschew the mode of spectatorship grounded in linear narrative knowable through human reason, and instead invite us to submit ourselves to the affects and intensities catalysed by the images onscreen. By allowing the ego to dissolve through an immersive contact with art, we are able to become one with the image, the distinction between subject and observer is annihilated; we become-image. Through this intensive, assemblage a new world born – the queer world of joyful becoming.

The films evoked above, through affective techniques such as the use of slow shutter speed, unexpected juxtaposition of aural and visual elements, or the “schizophrenic” cinematography where the camera swirls, drawn into unpredictable angles, allow us to shed our unified identity. These audio-visual works require viewers to eschew the mode of spectatorship grounded in linear narrative knowable through human reason, and instead invite us to submit ourselves to the affects and intensities catalysed by the images onscreen. By allowing the ego to dissolve through an immersive contact with art, we are able to become one with the image, the distinction between subject and observer is annihilated; we become-image. Through this intensive, assemblage a new world born – the queer world of joyful becoming.

|

SFragments of this article were initially developed at the Universty of St Andrews as Queer Temporality and Digital Touch in Taiwanese Digital Films. 7 January 2021. FM5002

|

Footnotes

|

1 Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will an Article on the Immediate Data of Consciousness, (London: G. Allen & Co., 1910).

2 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, (2000 [1972]); Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, (London: Continuum, (2005 [1980]). 3 Chrysanthi Nigianni, and Merl Storr, editors, Deleuze and Queer Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009. Deleuze and Queer Theory, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009) 4 Laura Marks, The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), pp. xi-xii. 5 Patricia Pisters, The Neuro-Image. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012). 6 Patricia MacCormack, Cinesexuality. (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2008), p.1. 7 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, p. 30. 8 Emma Cocker, “Kairos time: the performativity of timing and timeliness … or; between biding one’s time and knowing when to act.”. In: 1st PARSE Biennial Research Conference on TIME, Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing (Arts, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, 4-6 November 2015), p.3. |

9 Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I: The Movement-Image . (London: Bloomsbury Academic, (2013a [1983]); Gilles Deleuze, Cinema II: The Time-Image, (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013[1985]).

10 Pisters, Neuro-Image, pp. 303-306. 11 Warren Buckland, “Introduction”, In Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema, edited by Warren Buckland, (Oxford: Willey-Blackwell, 2009), p. 2.12 Deleuze, Cinema 2, p. 161. 13 Erin Manning, The Minor Gesture. (Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2016), pp. 1-2. 14Luce Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985 [1974]). 15 Lucy Bolton, Film and Female Consciousness, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 50. 16 Deleuze, Cinema 2, 195-196. 17 Hans Tao-Ming Huang, Queer Politics and Sexual Modernity in Taiwan, Hong Kong University Press, 2011), p. 26. 18 Deleuze, Cinema 2, pp. 131-160. 19 Deleuze, Cinema 2, pp. 282. 20 Deleuze, Cinema 2, p. 196. 21 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p. 280. 22 Jennifer Barker, The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), p. 136. 23 Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, Cambridge, (MA: MIT Press, 2001). |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barker, Jennifer. The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Bergson, Henri. Time and Free Will an Article on the Immediate Data of Consciousness. Translated by Frank Lubecki Pogson. London: G. Allen & Co., 1910.

Bolton, Lucy. Film and Female Consciousness. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Buckland, Warren. “Introduction”. In Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema, edited by Warren Buckland, 9-14. Oxford: Willey-Blackwell, 2009.

Cocker, Emma. “Kairos time: the Performativity of timing and timeliness … or; between biding one’s time and knowing when to act.”. In 1st PARSE Biennial Research Conference on TIME, Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing Arts. University of Gothenburg, Sweden, 4-6 November 2015.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, (2000 [1972]).

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema I: The Movement-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson & Barbara Habberjam. London: Bloomsbury Academic,2013[1983].

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema II: The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson & Robert Galeta. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013[1985].

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Continuum, (2005 [1980]).

Huang, Hans Tao-Ming. Queer Politics and Sexual Modernity in Taiwan. Hong Kong University Press, 2011.

Irigaray, Luce. Speculum of the Other Woman. Translated by Gillian C. Gill. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985 [1974].

MacCormack, Patricia. Cinesexuality. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2008.

Manning, Erin. The Minor Gesture. Durham; London: Duke University Press,2016.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media, Cambridge. MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Marks, Laura. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

Nigianni, Chrysanthi and Storr Merl, editors. Deleuze and Queer Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

Pisters, Patricia. The Neuro-Image. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2012.

Bergson, Henri. Time and Free Will an Article on the Immediate Data of Consciousness. Translated by Frank Lubecki Pogson. London: G. Allen & Co., 1910.

Bolton, Lucy. Film and Female Consciousness. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Buckland, Warren. “Introduction”. In Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema, edited by Warren Buckland, 9-14. Oxford: Willey-Blackwell, 2009.

Cocker, Emma. “Kairos time: the Performativity of timing and timeliness … or; between biding one’s time and knowing when to act.”. In 1st PARSE Biennial Research Conference on TIME, Faculty of Fine, Applied and Performing Arts. University of Gothenburg, Sweden, 4-6 November 2015.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem and Helen R. Lane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, (2000 [1972]).

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema I: The Movement-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson & Barbara Habberjam. London: Bloomsbury Academic,2013[1983].

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema II: The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson & Robert Galeta. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013[1985].

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Continuum, (2005 [1980]).

Huang, Hans Tao-Ming. Queer Politics and Sexual Modernity in Taiwan. Hong Kong University Press, 2011.

Irigaray, Luce. Speculum of the Other Woman. Translated by Gillian C. Gill. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985 [1974].

MacCormack, Patricia. Cinesexuality. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2008.

Manning, Erin. The Minor Gesture. Durham; London: Duke University Press,2016.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media, Cambridge. MA: MIT Press, 2001.

Marks, Laura. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

Nigianni, Chrysanthi and Storr Merl, editors. Deleuze and Queer Theory. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

Pisters, Patricia. The Neuro-Image. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2012.

Filmography

Echo Each Other. [Motion Picture]. Directed by Pin-ru Chen. Taiwan: Independent Production. 2016. Available online: https://www.gagaoolala.com/en/videos/943/echo-each-other-2017

Body at Large. [Motion Picture]. Directed by Ying Cheng-ju. Taiwan: Independent Production. 2012. Available online: https://www.gagaoolala.com/en/videos/98/body-at-large-2012

Adorable. [Motion Picture]. Directed by Cheng-Hsu Chung. Taiwan/UK: Royal College of Art. 2018. Available online: https://vimeo.com/391510151

Body at Large. [Motion Picture]. Directed by Ying Cheng-ju. Taiwan: Independent Production. 2012. Available online: https://www.gagaoolala.com/en/videos/98/body-at-large-2012

Adorable. [Motion Picture]. Directed by Cheng-Hsu Chung. Taiwan/UK: Royal College of Art. 2018. Available online: https://vimeo.com/391510151